By Dr Hima Bindu Kanoj

In the annals of Indian history, The Vijayanagara kingdom is one dynasty to be reckoned with. This, is not just because it was one of the most powerful kingdoms of the South which had contained the spread of the Musilm invasion, but also for its efficient overall development of society, arts, culture and heritage particularly, for the Hindu faith.

Not only as the most powerful empire whose vast kingdom spread all over the south, , it was also known as the rightly as the Golden Age of Arts, wherein arts like literature, sculpture, painting and dance flourished prosperously. Not only patronizing the arts, they made significant contributions to each of the art thus paving way to new artistic endeavors. When it came to literature, there was the development of the Prabandha literature, which gave in new insights to the poetic and the literary world. Sculptural development took form in shape of Raya Gopurams, introduction of the Kalyana Mantapas, which gave a totally new look to temple architecture.

The vegetable dyed paintings on the roofs of the inner temple Mantapas spoke all about the creative inflows in painting. It becomes even more interesting when it comes to dance, as dance was not just practiced as a singular art form, but, its existence could be found out in the other allied arts like literature, sculpture, music and painting, as an integral part either as an allegory, theme, or as a description. Not only just restricting itself to an artistic endeavour, dance reflected itself in the entire society by playing a vital role in all spheres of the society.

Dance, being an integral part of the society, found its place in the most important Centre of faith and learning, the temple. The temples had many roles to play in the Vijayanagara Empire. It was not just a place of worship, but it was a mark of the victory of the Hindu faith in the entire South Belt of India. Temples were built as a mark of commemoration of the victory campaigns, as patronage to the sculptural arts and most importantly as a center where all the people from different sections of the society could meet and interact and be a part of the festivities and important occasions of the society.

The sacred centre was full of vibrancy, and bustled with activity all day through. They were places of beauty portrayed through their architecture, mantapas, sculptures of various divinities, daily activities of the people, ornate embellishments and thematic presentations. Rituals were an important part of the temple. There were a huge number of people appointed for service of various rituals in the temples which involved the caretakers the priests, the administrative hierarchy, musicians, poets and then they were the temple dancers.

Being one of the highly patronized art form of the Vijayanagara times, it is only precise to say that the dancers were the important people of the society. Majorly, the dancers can be said to be divided into two classes, the court dancers and the temple dancers1 as per studies. These dancers were damsels of high expertise, extremely talented in all the Chatushasti Kalas (the 64 arts) and just not mere entertainers. Although both the classes of dancers enjoyed a respectable position in the society, it was the temple dancers who were in the topmost position in the society and had very special privileges in the society. With their high talent, they found place amongst not only the administrative hierarchy of Vijayanagara2, but also in the sacred centre, the temple.

Temple Dancers

The temple dancers were special dancers appointed by the king for the services of the temple known as Devadasis (meaning servant of the god). The Devadasis were treated as danseuse born for submission of their life to the deity. The rituals performed by them were in equal veneration with that of the rituals performed by the priests, in serving the deities of the temple.

The devadasis were called by different names like Sevikas, Dasis, Devarasanis, Gudisanis, Maddelakandru Rangabhogamuvaru, Bhogamuvaru, Paatri, Sani, Sumangali, Devara Basavi or Basavulu. This can be known through an inscription attached to the temple of Veereswara in Guntur District from the time of 1518 A.D which mentions that there were devarasani and devarabasavis Lingiakki and Yellipedanaagi appointed for the services of lord Veereswara. These terms were probably named after the kinds of services they offered to God.

Initiation ceremony

There was a certain procedure to become a Devadasi. The girl who was to be devoted to the temple was initiated into the ritual before she attained puberty. The senior Devadasis introduced the girl to the Yogakkar (teacher appointed for training the devadasi) and then she was granted a house called kudi or padi as her allowance for maintenance.

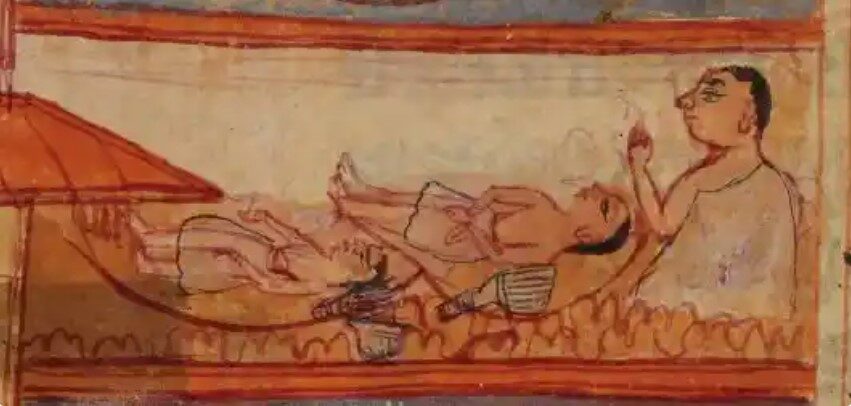

Then, on an auspicious day, the girl would be taken to the temple with all pomp and gaiety and the priest performed the talikettu or the marriage ceremony of the Devadasi with God. He would tie the sacred thread (Taali) on behalf of the God. Thus, the girl was solemnized as a Devadasi and she would be given all the necessary grants for her livelihood3. The temple dancers in the service of the temple mostly had no other duty except for the temple services. However, during celebration of major festivities like the Vasantotsav or the Mahanavami festivals, they danced along with other dancers and musicians in the capital.

Appointment of the Devadasis

The dancing girls were deputed by the king to render their services to the temple through dance and music. However, it was the choice of the dancer if she wanted to become a devadasi or a courtesan. There were hierarchies in the appointment of these temple dancers too. The dancing girlappointed as the main temple dancer was called Emperumanadiyar4. She was the one who performed in front of the main deity. Other than the main dancer, there was the Tiruvadisani5, who danced while the deity was taken out in procession. The dance master was called the Nattuvanar6. All of them offered their services through dance and music while all the rituals were being performed to the lord. Then, there were other dancers below these three, who served in their various capacities as processional dancers, singers, musicians, and servants to perform other certain rituals to god and offer their services to the temple.

The appointment of the Emperumanadiyar can be known through the inscriptional sources present in temple. An inscription from 1531 A.D. mentions Muddukuppayi and Nagasani were the damsels appointed for the services of the lord as Emperumanadiyar by Emperor Achyuta Raya at the temple of Tirupati7. These dancers had huge remuneration paid for their services and enjoyed all special privileges in the temple.

Duties of the temple dancers

Though all the dancers were considered temple servants, the duties varied according to the rank in the temple service. The Devadasis had their duties as per the rituals performed in the temple from morning to evening. The morning ritual of Suprabhatam started with the dancer singing and dancing while waking up the diety. The Suprabhata Seva was followed by various other rituals like the Archana, Deepa seva, etc. The main deity was fed by them. After all the main rituals for the lord were performed, the ritual of Rangabhogam was done where the devadasis used to sing and dance in praise of the deity in the Natya Mantapa specially built for the purpose.

Apart from these, the Devadasis used to perform other duties like holding a mirror to the god, decorating the temple with colours, etc. According to an inscription of 1382 A.D. in the Simhachalam temple in Vishakhapatnam, the temple damsels followed the ritual of holding a mirror while decorating the god.8 Another inscription of 1359 A.D. in the same temple mentions the devadasis offering camphor to the lord. The devadasis also accompanied the main priest while he carried the water from the Pushkarini in the temple premises to bathe the main deity as part of the daily ritual. As many of the rituals were done at a stretch in the whole day, the Devadasis often spent their entire day in the temple, and hence they were entitled to being offered the prasadam after it was offered to the main deity as their daily food allowance.

Apart from the temple duties, the devadasis participated in festivals and other important occasions in the kingdom and they were gifted with many valuables for their participation in them. Various foreign chronicles account for this. Dance was the most important activity in celebration and feasts and all dancers including the temple dancers were a part of it.

Domingo Paes, a Portugese traveller who visited Vijayanagara, confirms this during the occasion of one of the feasts he attended. He says, “For these feasts are summoned all the dancing-women of the kingdom, in order that they should be present; and also the captains and kings and great lords with all their retinues9”.

An epigraph of Krihsndevaraya ‘s time records that one actor NattuvaNagayya and one actress patri, atemple dancing girl enacted a play called Tayokonda natakam during the Virupaksha festival at Hampi and were awarded valuable gifts for their performance10.

Socio economic status

Regarding the socio economic status of the devadasis, they were not only respected by the kings, officers and the temple authorities for their expertise in art, but also for their consciousness towards development of the temple. As temple servants, the Devadasis enjoyed a reputable position and were quite rich. They made huge sums of donations for the development of the temple, thus earning special privileges, which otherwise are conferred upon only a few high profiled persons in the society. This included construction of mantapas, water tanks, and other contributions during different occasions to the temple11.

The devadasis were allowed to enter the precincts of the inner sanctum during certain special festivals. This was a privilege conferred only upon the kings and the dancing girls. They were also treated as special guests and honoured on different occasions.

An inscription dated 1535 A.D mentions that, Chikkayasavayi, and her younger sister, the two damsels at Tirupati, during the reign Achyuta Raya, were called upon to inaugurate a festival called Chittarai Vishu (Tamil New Year Day), at the Tirumala Temple12. This shows the prominence given to the dancers on the important festivities of the temple.

In another inscription dated 1546 A.D, a dancing girl, Tiruvenkata Manikkam, was granted a palanquin as a token of honour for the services rendered by her to the Tirumala Temple13. Another inscription states that on the name of Elli Tirumagal, a dancing girl, the temple authorities were authorized to distribute prasadams to the donors and devotees at the temple14. All the above inscriptions indicate that the devadasis had a reputable position on the society.

The devadasis lived in the houses allotted by the temple authorities and enjoyed all luxuries. The maintenance allowance for the house which was called sule15 was taken care by the temple. The tax collected on this maintenance was spent in other benefits of the society.

The Sculptural Representations

The temple dancers made their presence felt in every ritual, celebration and activity of the temple. Forever carved on the walls of each and every temple of Vijaayanagara, the temple sculptures (apart from the inscriptional sources) too help throw light on the different dancers dedicated to the temple. A common pattern is seen in the temples of Vijayanagara is that the inner Mantapas of the temple have figures of images of heavily ornamented and dressed dancing girls in various movements of dance and also performing different rituals to the deity. The Garbhagriha, Rangamantapa, Mahamantapa and the Natyamantapa, which are considered the inner precincts of the temple depict pillars of dancers carved with various other themes of celestials beings. This gives strength to the point that these might be the imageries of dancers are those of the Devadasis appointed to perform the main rituals of the temple, and hence given a place in the inner precincts of the temple.

Then, they are Kalyana Mantapas and the VasantotsavaMantapas and the Pradakshina Parkaras of the temple which depict groups of dancers in much more simpler costumes, jewelry and in movements depicting more of enthusiastic jumps, vibrancy and sometimes acrobatic in nature. These sculptures are majorly carved on the Adhisthanas (base) of the Kalyana Mantapas and outer Prakara walls of the temple, which again substantiate the fact that these dancers might be the ones who participated in the daily processional activities, festivities and serving the processional deities of the temple..

Be it any class of dancer in the temple, the dancers were treated as women of position, and given a strong foothold in the temple activities and the dancers made their presence felt in every important occasion with grace and honoured for their generosity and expertise in the art form.

It is only right to say that these dancers of Vijayanagara seem to have extended the purpose of dance mentioned by Bharata in the Natya Sastra,

“Dukhaartaanaam Sramartaanaam Sokaartaanam, Tapasvenaam,.

Visraanti Jananam Kale, Natya metadhabhavishyati”16

Dance is the solace to the hardworking people, the ones who are stuck in grief and even the mendicants who search internal happiness of the soul. Be it anybody class, creed or caste of the society, without the disparities of the society, dance is the one which brings happiness to one and all.

Proving this, the dancing damsels of the temple were dancers not for entertainment, butbeyond, wherein they put their heart and soul in the development of the temple and the society through their dance all their life.

Citations

- Katragadda, Lakshmi. 1996. Women in Vijayanagara- Women in 16th century. (AStudy of Tuluva Dynasty). New Delhi: Delta Publishing House : 35. ↩︎

- Satyanarayana Kampbhampati, 2007. Andhrula Sanskruti charitra, Hyderabad: Hyderabad Book Trust : 146. ↩︎

- Ibid : 40. ↩︎

- Vasudevan, C.S. 2000. Temples of Andhra Pradesh. New Delhi: Bharatiya Kala Prakashan: 193. ↩︎

- Ibid ; 194. ↩︎

- Ibid ; 194. ↩︎

- Ibid :195. ↩︎

- Katragadda, Lakshmi. 1996 : 41. ↩︎

- Ibid : 357. ↩︎

- Saletore, B.A. 1934. Social and Political Life in the Vijayanagara Empire. Vol – I. Madras: B.G. Paul & Co : 169. ↩︎

- Saletore, R.N. 1936 : 203. ↩︎

- Vijayaraghavacharya, V. 1998. Tirumal Tirupati Inscriptions. Vol- I- VIII. Tirupati: TTD Publlications . ↩︎

- Ibid : Vol- IV :78. ↩︎

- Lalitha, Vakulabharanam. Pramila Reddy, Malkapalli. 2007. Devadaasi Vyavastha. Hyderabad: Asmita :355. ↩︎

- Vijayaraghavacharya, V. 1998 Vol- V. ↩︎

- Lalitha, Vakulabharanam. Pramila Reddy, Malkapalli.2007:97. ↩︎