Abstract: India has been a land of constant artistic developments with influences of region, religion etc. Art has been an integral part of India since ancient times to present. Several dynasties have commissioned art forms for their development and continuation. Similarly, the influence of Buddhism on art was quite significant. In the developmental stages, several influences were recognised in the art form such as Gandhara, Mathura and Amravati, which became distinct school of arts. However, Buddha was not always depicted in the form what we see today, the depiction went through several stages of development. The present paper examines the evolution of Buddhist art, transitioning from aniconic depictions of the Buddha’s life and teachings to iconic representations. The analysis of the archaeological evidence, inscriptions, and stylistic transitions will enable to understand the religious, cultural, and sociopolitical factors influencing this transformation. For the present study archaeological evidences and artistic depictions will be undertaken from the key sites including Sanchi, Gandhara, and Mathura to demonstrate regional variations and artistic innovations.

Buddhism: An Introduction

Siddharth Gautam, later known as the Buddha, was born into the royal family of Kapilvastu, a small kingdom situated in the Himalayan foothills. His conception and birth were regarded as miraculous, and sages at the time predicted that he would achieve one of two destinies: becoming a universal conqueror of the physical world or a spiritual saviour who would conquer the minds of humanity (Huntington, 1985). It was the latter destiny that he fulfilled, embarking on a spiritual quest that would lay the foundation for Buddhism. He renounced the luxuries of his royal life in pursuit of ultimate truth and purpose. Initially, he practiced severe asceticism, a common path for spiritual seekers in ancient India, but abandoned it after six years, recognizing it as an ineffective means to enlightenment. Subsequently, he adopted the Middle Path (Madhyama path), a philosophy that rejected both indulgence and extreme austerity. This approach led him to meditate beneath the Bodhi tree, where he ultimately achieved enlightenment, earning the title of Buddha, or ‘Enlightened one’(Williams, 2009).

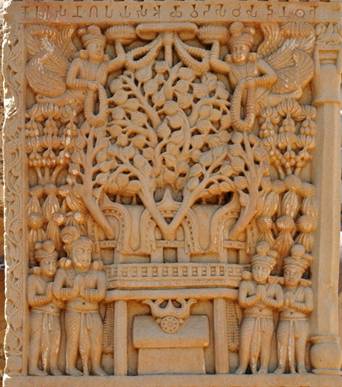

Buddhism, as proposed by the Buddha, advocates a balanced life centred on good thoughts, intentions, and ethical living. The ultimate goal is the attainment of Nirvana a state of liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth, or samsara.(Strong, 2004). During his life, Buddha travelled extensively, spreading his teachings and amassing a significant following. Upon his death, his body was cremated in accordance with customs. The relics of his cremated remains were divided and enshrined in relic caskets, which were interred within Stupas (large hemispherical structures that became central to Buddhist monastic complexes) (Cunningham, 1879). The Stupas (Fig 1.) play a vital role in propagation of Buddhism and understanding the development of the Buddhist art. The architectural design of stupas incorporates ritual circumambulation paths enclosed by railings, with entrances marked by gateways oriented to the cardinal directions. These features not only facilitate meditative and spiritual purpose but also a space for the laity to understand the teachings of Buddha through visual depiction. (Rowland, 1974).

Buddhist Art

Art has always been a medium of propagating ideas to the laity. Indian Art is not just for the sake of art but comprises deep symbolic and metaphysical meaning. Stories and their visual depiction has been useful till date to educate about certain important ideas and keeping them in the mind stored for long. Similarly, Buddhist art has played a crucial role in communicating religious teachings and fostering devotion.

During the first century BCE, Indian artists began a transformative shift in their choice of medium, transitioning from the use of ephemeral materials such as brick, wood, thatch, and bamboo to the more enduring medium of stone. This change coincided with the increased patronage of Buddhist architecture, particularly stupas, which emerged as the focal points of monastic complexes and pilgrimage sites. This transition was not merely a technical innovation but a reflection of the socio-religious and artistic developments of the period (Huntington, 1985). Stonework offered durability and allowed for intricate detailing, which elevated the artistic quality and narrative power of Buddhist structures. Railings and gateways made of stone were added to existing stupas, transforming them into elaborate monuments that conveyed Buddhist teachings through visual storytelling. These stone embellishments were often adorned with relief sculptures, meticulously carved to depict scenes from the Buddha’s life and previous incarnations. The inclusion of these reliefs served both didactic and devotional purposes, enabling worshippers to engage with the narratives while circumambulating the stupa (Cunningham, 1879).

It marked the beginning of a narrative tradition that used visual media to transcend linguistic barriers, making Buddhist teachings accessible to diverse communities across India and beyond. Furthermore, the monumental stone gateways and railings became archetypal features of Buddhist architecture, symbolizing both spiritual protection and the threshold between the secular and sacred realms (Williams, 2009). The adoption of stone was an add on enabling the preservation of these narratives, ensuring their continuity and influence over centuries.

Aniconic Phase of Buddhist Art

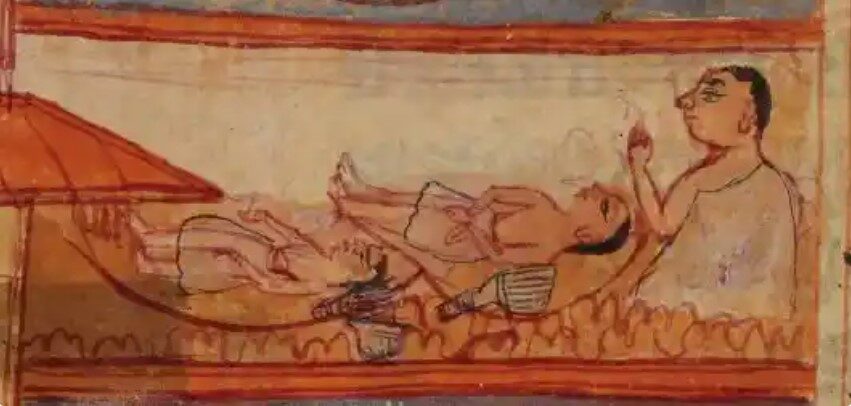

Aniconic means symbolic representation or devoid of human-like depiction. The aniconic phase of Buddhist art is characterized and identified by the absolute absence of anthropomorphic or human- like depictions of Buddha. Several other symbols were utilised to convey his presence and teachings. The common motifs which were employed repetitively such as the Bodhi tree, symbolizing the Buddha’s enlightenment; the empty throne, indicating his presence in absence; the dharma wheel, representing the teachings of the Dhamma; and the stupa, which served as a powerful symbol of nirvana and the Buddha’s final liberation (Rowland, 1974).

Sanchi and Bharhut stupas provide valuable insights into the artistic practices of this period. The reliefs at the Sanchi Stupa in Madhya Pradesh depict pivotal moments from the Buddha’s life, such as his enlightenment, using symbolic imagery like the Bodhi tree. These carvings masterfully communicate complex narratives while maintaining aniconism, allowing viewers to engage with the Buddha’s story on a conceptual level (Huntington, 1985). Similarly, the Bharhut Stupa is renowned for its intricate panels illustrating Jataka tales—stories of the Buddha’s past lives. These carvings not only emphasize moral and ethical teachings but also integrate inscriptions identifying the scenes, making them accessible to diverse audiences (Cunningham, 1879).

The aniconic phase reflects early Buddhist religious and philosophical contexts, particularly teachings on impermanence (anicca) and selflessness (anatta). These principles may have discouraged the creation of anthropomorphic depictions, as such images could be perceived as contradictory to the Buddhist rejection of ego and permanence. Instead, the focus on symbols and abstract representations encouraged contemplation of universal truths and principles, fostering a deeper engagement with the teachings rather than their physical manifestations (Williams, 2009).

Buddha as Bodhi tree, Sanchi Stupa

Buddha worshipped as Stupa (Sanchi and Bharhut)

Buddha as Dhamma Chakra and Buddha pada (footprints)

Transition to Iconic Forms

The fourth Buddhist council held at Kundalavan in Kashmir under Kushan ruler Kanishka in 72 CE marked the remarkable transition in the depiction of Buddha in artistic forms. Kushan Empire played a pivotal role in fostering cultural and artistic exchanges through its expansive trade networks, particularly along the Silk Road. These exchanges introduced new artistic paradigms to Buddhist centres, influencing the evolution of Buddhist iconography. The interaction of Indian, Hellenistic, and Central Asian artistic traditions during this period marked a significant shift from aniconic to iconic representations in Buddhist art, reflecting the changing religious and sociocultural landscape (Huntington, 1985).

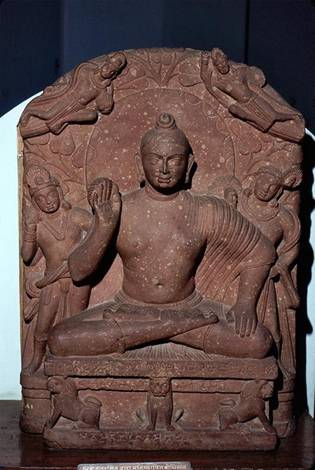

The Gandhara School of Art emerged as a prime example of this synthesis, flourishing in the Gandhara region (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan). It became a melting pot of Greco-Buddhist art, where Hellenistic styles blended seamlessly with Buddhist themes. Early Buddha images from Gandhara exhibit pronounced Greco-Roman influences, including wavy hair, serene facial expressions, and drapery. These features emphasized naturalism and grace, creating a relatable and humanized portrayal of the Buddha. Such artistic choices not only reflected the influence of Hellenistic ideals but also served to make the Buddha’s image accessible to a culturally diverse audience across the Kushan Empire’s vast territories (Rowland, 1974).In contrast, theMathura School of Art drew from indigenous Indian aesthetic traditions, emphasizing robust and sensuous forms. Mathura’s sculptors favoured red sandstone as a medium and developed a distinctive style that celebrated Indian iconography. Buddha figures from this school prominently featured the ushnisha (a cranial protuberance symbolizing wisdom) and the urna (a forehead mark representing spiritual insight) (Cunningham, 1879).

Anthropomorphic depictions humanized the Buddha, enabling lay practitioners to relate to his teachings and fostering a devotional culture more. This transformation aligned with the rise of Mahayana Buddhism, which emphasized the Buddha as a compassionate saviour figure. Iconic representations facilitated a more personal and emotional connection between the Buddha and his followers, encouraging practices such as image worship and pilgrimage to sacred sites (Williams, 2009).

Fig. 5 Buddha, Gandhara School of Art

Fig. 6 Buddha, Mathura School of Art

Discussion and conclusion

The transformation from aniconism to iconic representation in Buddhist art reflects a dynamic interplay of religious, cultural, and political influences. Initially, aniconism, characterized by symbolic representations of the Buddha through motifs like the Bodhi tree, stupa, and dharma wheel, aligned with early Buddhist teachings that emphasized abstract principles over physical depictions. However, the emergence of iconic representation marked a significant evolution, driven by cultural exchanges facilitated by the Silk Road, religious developments within Mahayana Buddhism, and the patronage of powerful rulers such as the Kushan Emperor Kanishka I. Iconic imagery humanized the Buddha, fostering emotional connections and making Buddhist teachings more accessible to lay practitioners.

Aniconic art appealed to monastic and intellectual audiences through its abstraction and focus on universal principles, while iconic art introduced a relatable and dynamic dimension that enhanced its appeal to broader audiences. Regional variations, such as the Greco-Indian synthesis in Gandhara, the indigenous aesthetics of Mathura, and the transitional styles at Amaravati, underscore the diversity and adaptability of Buddhist artistic traditions. These developments played a pivotal role in the religion’s expansion, as iconic imagery and influenced other art forms.

The transition from aniconic to iconic art thus represents a dynamic period in Buddhist history, shaped by intercultural exchanges and evolving religious practices. The stylistic differences between Gandhara and Mathura highlight the regional diversity of Buddhist art, while their shared focus on iconic imagery underscores its central role in promoting the spread and accessibility of Buddhist teachings.

References

- Behl, B. L. (1998). The Ajanta Caves: Artistic Creativity in Buddhist Cave Temples. Thames & Hudson.

- Cunningham, A. (1879). The Stupa of Bharhut: A Buddhist Monument Ornamented with Numerous Sculptures Illustrative of Buddhist Legend and History in the Third Century BC. W. H. Allen.

- Dehejia, Vidya. Indian Art. London: Phaidon, 1997.

- Huntington, S. L. (1985). The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Weatherill.

- Mitter, Partha. Indian Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Rowland, B. (1974). The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. Penguin Books.

- Strong, J. S. (2004). Relics of the Buddha. Princeton University Press.

- Williams, P. (2009). Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. Routledge.

- Zin, M. (2013). “The Evolution of the Buddha Image: A Study in Buddhist Art and Iconography.” Journal of Buddhist Studies, 42(1), 19-35.

Dr Pratishtha Mukherjee is an archaeologist and heritage scholar specializing in ancient Indian sculpture, iconography, and temple architecture. She serves as an Assistant Professor at Rishihood University. A PhD graduate from The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, her work explores the sculptural traditions of Yakṣa figures in North India. She has held roles with the ASI, National Museum, INTACH, and is a recipient of the Sri Shankara Swami Bharati Fellowship and the IKS Research Grant for her contributions to Indigenous Knowledge Systems.