Introduction

The fundamental principle of Jainism is that entire universe is made up of 6 substances, out of which ‘jiva’ and ‘ajiva’ are important to understand. Jiva or the soul is the living entity while ajiva is non-living matter of the universe. This philosophical or spiritual soul in Jain philosophy attracts all sorts of karmic matters which either liberates the soul or become the cause of its destruction. Therefore, the main goal among Jains is the human endeavor for liberation from karmas, the emotions, passions, and all sorts of boundations. So, for this purpose, various practices have been followed for thousands of years. One such practice is Sallekhana, which is the final step towards purification of the soul and liberation from the karmic cycle.

According to Jain philosophy, every living being can break the cycle of birth and death to attain liberation. But for that purpose, they have to get rid of all the karmas which cling to their soul. The practice which deals with purification of soul and self-introspection, when the end is nearing, is Sallekhana. Death is the ultimate reality of every living being’s life. How should a wise man face death when it is nearing? In the Fifth lecture of the Uttaradhyayanasutra (vv. 2, 3, 16 to 19, 29 to 31- ‘Jain Sutras, translated by Herman Jacobi, Sacred Books of the East’, Vol. 45) it is stated that there are two ways of facing death: death with one’s will and death against one’s will. “Death against one’s will is that of ignorant men, and it happens (to the same individual) many times. Death with one’s will is that of wise men, and at best it happens but once. Sallekhana in simple terms means facing death (by an ascetic or a householder) voluntarily when he is nearing his end and when normal life according to religion is not possible due to old-age, incurable disease, severe famine, etc. after subjugation of all passions and abandonment of all worldly attachments, by observance of austerities gradually abstaining from food and water, and by simultaneous meditation on real nature of self until the soul parts from body. (Tukol, 1976)

The records of this practice come from sources like Ratnakarandaka of Samantabhadra: “When overtaken by calamity, by famine, by old age, by incurable disease, to get rid of the body for dharma is called sallekhana. It is also known by names such as samlehana, santhara, Samadhi-marana or sanyasa-marana. One should by degrees give up solid food and take liquid food; then, giving up liquid food, should gradually content himself with warm water; then, abandoning even warm water, should fast entirely; and thus, with mind intent on five salutations, should be every effort quit the body. Other mention of sallekhana is found in Dharmamrita Asadhara. Other than written records this practice also finds a mention in archaeological sources like the epitaphs with synonymous terms like samadhi and sanyasa. The word used for epitaph is nisidige or nishidhi, while in other regions it is also known as Palli, Nasiya/Nishiyaji, Chhatri or Tonk. These are the records of the people including monks, nuns, kings, ascetics and even householders in the form of memorials who underwent the practice of sallekhana at different locations under different circumstances and at different time periods even back to seventh and eighth centuries. Several such memorial stones or nisidige have been found from several regions of Karnataka and neighboring states. The region of Shravanbelagola yields a lot of such records.

Further is an analysis of the advent of Jainism in Karnataka and the locational analysis of the memorial stones or nisidige, the inscriptions and finally the critical analysis of the sallekhana practice in today’s world.

Advent of Jainism in Karnataka

The advent of Jainism is Karnataka is mentioned in various records and its growth, the patronage received from ruling dynasties and contribution in development of Kannada literature are known through grants and other records. The tradition regarding the migration of the Srutakevali Bhadrabahu with his disciple Chandragupta Maurya becomes an important incident in the history of Jainism in South India. Bhadrabahu who was the last Srutakevali, predicted a 12-year drought and famine in north India after which the Jain community, under his leadership migrated to south. Chandragupta, the first Mauryan emperor, abdicated the throne and became the disciple of Bhadrabahu. The site of Sravana Belagola is very important as the Srutakevali spends his last days here with his disciple Chandragupta who after some time also died by the Jain rite of sallekhana or starvation. Various facts are produced to support this tradition, the smaller hill at Belagola is said to derive its name Chandragiri from the fact that Chandragupta lived and performed penance here. A cave called as Bhadrabahu cave on this hill contains srutakevali’s footprints, a place where he died. Some other inscriptions also mention the srutakevali and his disciple and the spread of Jain religion. Literary works like Brihatkathakosa, which is a Sanskrit work by Harishena also mention Chandragupta as the disciple. Inscription no. 1 at Sravana Belagola talks about the whole legend regarding Bhadrabahuswami, his abilities and him taking Samadhi during his end days.

Some scholars are of the view that Jainism came much before arrival of Bhadrabhau and discard the Bhadrabahu-Chandragupta tradition. But looking at lithic evidence like structures, epigraphs and sculptures, one cannot deny the widespread presence of Jain philosophy in Karnataka for a long span of time. One such striking example is the nisidige or the memorial stones which show us the prevalence of such a practice which raised certain questions where one can relate it with either spiritual awakening of one’s soul or the extreme path to shed karmic matters.

Nisidige stones or memorial epitaphs

Setting up Nishidhi or the post mortem memorials was a practice of dedicating a part or the whole of a holy structure, a pillar or mandapa of a temple in the memory of a deceased person. Some memorial stones were confined to the description of the event itself or only the record of the death of the person. But if we take the epigraphs from Sravana Belagola, it becomes evident that this practice was fairly common in those days. The inscriptions found from this place are engraved on the pillars of the halls of the holy structures which determine the fact that people mentioned in these memorials held some sort of important position. These Nishidhis were erected by the family members or devotees of the deceased as parokshavinaya, which is a gesture of reverence.

P.B.Desai points out some epigraphs at Sravana Belagola (No. 168, 272, 273, etc.) which are themselves recording the death of a person are referred to as Nishidhis and is not sure whether these Nishidhi memorials should be called a nominal or spiritual Nishidhis. All the epigraphs found within this region have Sanskrit language and Kannada script of early and medieval periods. Like the other Jain inscriptions, the Nishidhi memorials also begin with some hymn or some verses in the praise of the Arhat. There are different types of Nishidhi memorials based on location, content matter and placement. The earliest sallekhana inscriptions are from Sosale in Mysore district in Karnataka dated 500 A.D. from Araballi in Bellary district (620 A.D) and from Kalavappu dated 6-7 A.D. In few cases period of fast is mentioned, like three days in 59 of them, twenty-one days in 33 and even one month in many others. These epitaphs range in date from about 600-1809. Sixty- four out of eighty inscriptions commemorate the death of men, mostly monks and sixteen of women, mostly nuns. Inscriptions number 1 and 11 have some historical importance as they seem to be earliest records at Belagola. Other than date and content matter, locational analysis is another important aspect of these memorial epitaphs.

Locational Analysis and Types of Nishidhis

As talked about earlier, these Nishidhi stones are placed at some important places of an important structure like a pillar or mandapa of a temple. There are more than 270 nishidhis found at Shravana Belagola, 70 at Koppala, 40 at Dharwad and other at Mysuru, Chamarajanagar, Belagavi, etc. The site of Sosale was a great centre of Jainism back in the days from where a Nishidhi slab was found from Ammanavara temple assigned back to 5 A.D. on paleographical basis. Record is in Kannada script and Sanskrit language which talks about Gunasena who at 65 years of age became a Nirgrantha by giving up his robes and performed sallekhana. This is one of the oldest examples of such memorials from Karnataka. Another is a site called Araballi, which is a small place with hills and natural caves, located in Harapanahalli Tq. Bellary district. This one is carved on a boulder recording the names of some of the monks who did by observing sallekhana. A third important site is that of Kalvappu, here ‘Vapra’ means a hill and ‘Kata’ means sepulcher, a burial mound, a hillock of tombs. The hilly terrain and the natural caves attracted many ascetics and householders to spend their last days at this site. The earliest inscription here, inscription no. 1, is a Nishidhi inscription which records the death by Samadhi of a Jain saint Prabhachandra. Many Nishidhis at Chandragiri hill only speak about the name of the person, the vow he took and the disciples who commemorated the memorial. Whether the person was from society or the sangha, who are detached from the world, followed the aim of sallekhana, detaching themselves from pride, passion and previous status.

Later, instead of epitaphs, these memorials were represented with footprints. Presently also some of the most revered personalities are remembered and worshipped in the form of their footprints on the place of their Samadhi. This is one way of celebrating the memory of the deceased and remembering them forever. Other than Jain faith, foot marks of the holy persons are regarded very sacred in other religions also. Sammed Shikharji, which is a Jain tirtha in Bihar, is the finest example of is the finest example where the footprints of 20 tirthankaras are worshipped. Bhdrabahu cave at Chandragiri houses the footprints of Bhadrabahu where he spent his final days. Footprint memorial of Pallakki Gundu is established on the hilltop at Koppal, which is another such example of death by sallekhana, as mentioned in an inscription nearby.

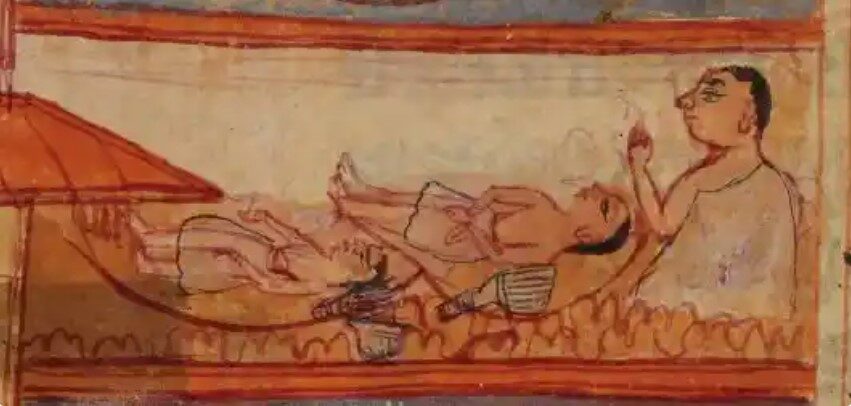

Other than the epitaphs and the footprint memorials, there are certain Nishidhi sculptures. Nishidhis evolved and took form of inscribed slab with artistically carved sculptures on it. Usually, the lower panel depicts an acharya with a pinchi and kamandalu, initiating a person seeking sallekhana. Others image show, a person after death and a scripture on a tripod like stand. Inscriptions on the lower panel give details like regnal year of king, vows, etc. The earliest example of the nishidhi sculpture comes from Meguti Jain temple at Aihole in Karnataka, datable to 7th C, A.D. In this sculpture, Mahavira is shown seated with three lions. The images of acharya with pinchi, which is a peacock feather wishbroom, and kamandalu are shown. The person seeking sallekhana is shown in anjali mudra and is seated in a yogic posture.

Other category includes Boulder Memorials. These are carved on large boulders which are easily visible like at the entrance of a temple, hilltop, etc. Sometimes these are decorated with elaborate artistic work. Boulder is known as Gundu in Kannada. Siddara Gundu is a boulder at Akanda Bagilu on a large hill at Sravana Belagola which includes a number of inscriptions which depicts a number of people who took Samadhi here.

Nishidhi Pillars are the free- standing pillars usually found in front of the Jain Basadis, which is a unique feature of Jain architecture known as Manastambas which bear the memorial records. One of the best examples of this is Kuge Brahmadeva pillar at Chandragiri in Sravanabelagola.

This pillar has the inscription of Marasimha who died at Bankapura after observing the aradhana vow for 3 days and he was eulogized as ‘Ganga Diamond’ for his heroic attributes. The Manastabmba was erected at Chandragiri after he attained Samadhi. Thus, the memorials were also erected at faraway places.

Memorial Columns or Mantapas are generally found in the temples or near the basadis. Sravana Belagola Mantapas, at the Chandragiri hill, are constructed for the nishidhis with pillared roof. These are called Nishadhyalaya. Some important Mantapas include Rastrakuta Manatapa constructed in honor of Rastrakuta monarch Indra IV. This inscription eulogizes the king’s achievements who died by sallekhana. Other examples include, Mahanavami Mantapa, Machikabbe Mantapa, etc.

Some Inscriptions

The content matter of these inscriptions includes details like language, period, person’s profile, guru parampara, mention of different sanghas, actual feelings of the witnesses of the person undergoing sallekhana, about the person’s social and economic status, account of king’s area of kingdom and administration, description of Jainism, etc. Various reasons, as per the nishidis, are also mentioned for which people practiced sallekhana. These are, ill health, old age, death of husband/ mother-in-law/ daughter, to attain salvation, durbiksha or famine, upsarga or trials and tribulations by enemies, snake bite, etc. These nishidis are seen in poetic format. Inscriptions at Shravana Belagola cover the records of people from various backgrounds, like ascetics, royal family members, householders, etc. Some of the inscriptions are placed on the walls of the temples, dedicated to a tirthankara, these epigraphs are issued by someone known to the person who undertook the vow of sallekhana.

Nishidhi, a 14th-century memorial stone depicting the observance of the vow of Sallekhana with old Kannada inscription. Found at Tavanandi forest, Karnataka.Among the earliest records at Belagola, inscription number 1 records the death of a Jain guru Prabhachandra. It was started with the verses in the praise of Vardhamana Mahavira and a line of number of Jain teachers who succeeded him. They were, Gautama Ganadhara, Loharya, Jambu, Vishnudeva, Aparajita, Govardhana, Bhadrabahu, Visakha, etc. An acharya named Prabhachandra desired to accomplish Samadhi on the mountain named Katavapara. He dismissed the entire sangha and mortified his whole body on cold rocks after which 700 rishis also accomplished Samadhi.

No. 11 is the epitaph of Arishtanemi. It opens up with a statement about an acharya, apparently Arishtanemi, came to south with his disciples and further points out that he died on the Katavapra hill where Dindika was the witness. A lady named Kampita, who is possibly the queen of Dindika, is also mentioned as doing honor to the acharya. There is also a list of monks whose death is mentioned in remaining epitaphs. This includes names like Baladeva-muni, son of Kanakasena; Tirthada-goravadigal; Ullikkal-goravadigal, and many more. Among all these epitaphs only inscription number 21 gives the name of the engraver, dated around 700, the name given is Pallavachari.

Some later epitaphs like no. 68 which is dated back to 950, records the death of Vaijabbe, daughter of Bettadavo; no. 136 records is of Sayiabbe-kantiyar, a female disciple of Kumaranandi-bhatara and some later records of dates, 1100, 1311, 1316, 1372 and so on. An epitaph at Belagola, dated 1809, mentions death of Ajitakirti at the Bhadrabahu cave. Some of the longer and elaborate epitaphs mention the list of gurus in succeeding order. The earliest of these records is the epitaph 127, which mentions the death of Meghachandra-trividya-deva in 1115. It also mentions the sangha and guru of the person. An example of death of a nun, Srimati-ganti in 1119 is also mentioned and her epitaph was established by her disciple, Mankabbe-ganti.

Two inscriptions are seen on the pillar of a temple at village Karadalu in Tiptur Taluka. Both are dated about 1174 A.D. First one mentions the death of a woman named Haryyale. She got the puja performed and took the sandal water. In the presence of Sri Jinendra she loudly repeated the five expressions (namokara-mantra), conquered all her desires and died by Samadhi.

Another important inscription, no. 254, gives information about the transmission about the formation of sangha, and gives the record of the death of a guru named Pandita. This inscription also gives information on succession of gurus and ends with the mention of Pandita’s disciple who set up the epitaph. The last epitaph no. 258 also refers to formation of sanghas and death of Srutamuni in 1432 and also mention of death of his four predecessors by the rite of Samadhi. This inscription is also an example where cause of the death by Samadhi, which is suffering from an incurable disease, is mentioned in great detail.

Three nishidis were discovered recently at Kurdigi which is a sculptural memorial. First one is divided into 3 parts, these include carvings of tirthankaras flanked by chowri bearers. A monk is shown preaching sallekhana vow along with the carvings of holy books. Most of the details of this inscription are worn out. Other two are also sculptural memorials.

Other than these there are many other such examples which highlight the importance and extent of this practice of sallekhana in Karnataka which also suggests the beliefs and practices of people from different walks of life during different time periods along with the spread of Jain ideas and traditions.

Sallekhana practice- an analysis

As talked about in the beginning, sallekhana is a practice of facing death voluntarily due to various reasons like old age, ill health, severe famine, etc. It is one of the most sacred practices of Samadhi marana or getting detached from material world by leaving mortal body and the karmic matters behind for the purification of supreme atman or soul. The evidence of this practice is seen through the nishidhi memorials found from different areas of Karnataka and the records of number of people who actually performed this rite during a long span of time. Not only Karnataka but this practice was also prevalent in other parts and during much later time period like in 1912, a monk at Ahmedabad underwent the rite of sallekhana after fasting for 41 days. Another such instance was seen in 1973, at a place called Gajapanth in Maharashtra, where a monk named Sudharmasagar Muni followed the path of sallekhana after slowly and gradually giving up solid foods and only taking up liquids like milk and water and later leaving that also and during final stage he used to spend his time in silence and spent his time in reading scriptures. His peace of mind went on increasing during this time.

Many such incidents were seen during a long span of time. In 2015, the Rajasthan High court, in its ruling, declared santhara or sallekhana illegal, stating that it was a form of suicide which is punishable under the Indian Penal code. However, the Jain community protested against the High Court’s ruling, asserting that sallekhana is not suicide but a devout religious practice. Later, the ruling to ban sallekhana was stayed by the order of Supreme Court but it raised several questions regarding religious freedom and right to life. It is important to understand the difference between a suicide and the practice of sallekhana. Suicide is killing oneself by means employed by oneself. The Sanskrit word used here is Atmahatya or self-destruction. A victim of self destruction is either the victim of his mental weakness or of external circumstances which he is not able to circumvent. (Tukol, 1976) All these reasons act as a sudden impulse for a person to take this extreme step.

Kautilya had mentioned various reasons for suicide in Arthshastra which includes disputes, professional competition, and anger. In today’s world there are now greater numbers of cases of unbearable emotional stresses and strains than before which are major driving forces for such actions. However, the practice of sallekhana has been followed since centuries and is not a new phenomenon. Sallekhana vow could only be taken under right intentions, situation, the means of taking the vow and the outcome or action of its consequences. The person adopting the vow wants to be liberated from the bondage of karmas from the soul and thus should get rid of all worldly attachments and possessions. Contrary to suicidal intention, there is no urge to put an end to life under pressure or frustration and by violent means. The intention needs to be pure and not impulsive. For example, in case of Bhadrabahu and his disciples, who migrated from North to South on account of apprehension of severe famine of 12 years and Bhadrabahu adopting the vow when he felt that his end was near, is indicator of the idea that the vow can be adopted under a calamity, a famine, or an incurable illness. Moreover, the vow has to be adopted only under the consent and guidance of a guru, both joyfully and voluntarily, and should not be forced upon by someone under any circumstances. The consequences of death by sallekhana are not hurtful nor sorrowful since there no violence or self-harm involved.

Thus, there is nothing common between sallekhana and suicide, except that in both cases there is death. And death which is not a result of himsa or violence but of self-reflection and penance.

Conclusion

The practice of sallekhana, though with very deep philosophical and religious importance, remains a critical and controversial topic among scholars and critics, mainly because of its nature of embracing death voluntarily. Western writers stated that it is suicide by starvation. B. Lewis Rice, who first collected and published the sallekhana inscriptions, heavily critiqued the practice itself. Similarly, some satirical remarks were made by Mrs. Sinclair Stevenson about the practice, while talking about the aspect of non-violence in Jainism and questioning such a practice while comparing it with suicide. T. K. Tukol has refuted these arguments, that the person undertaking the vow does not merely lie down like a dead log and do nothing or starve for no reason, instead, it is much more than that and is only performed by someone, like an ascetic, who has preached and practiced religion all along, under certain circumstances (earlier talked about) and after conquering all his desires is detached from world and for him/ her death is final stage for liberation. Hermann Jacobi also refuted the conception that sallekhana is suicide.

The inscriptions with information about sallekhna have shown that people from all walks of life, like kings, queens, householders, generals, monks, nuns, ascetics, etc., adopted the vow under the guidance of a spiritual mentor. These Nishidhi inscriptions here become very important because they not only talk about the sallekhana practice but it’s connection with people of all sorts of backgrounds. The people who died under this vow were revered or remembered forever in stone in the form of memorials where the placement of the inscription helps us in understanding the position of the person to whom it belonged. For example, a temple, a house, a cave, a boulder, etc.

Overall, these inscriptions gave us an idea of extent of Jainism in Karnataka from times of Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya to later times and the vast area which it covered.

Therefore, in his commentary on Tattvärtha-Sūtra, Pūjyapada says: “A person who kills himself by means of poison, weapons etc. swayed by attachment, aversion or in-fatuation, commits suicide. But he who practises holy death is free from desire, anger or delusion. Hence it is not suicide.”

Bibliography

- Epigraphia Carnatica; Volume II, Sravanabelagola, Institute of Kannada Studies, Mysore -1973

- P. B. Desai; Jainism in South India and Some Jain Jain Epigraphs, Solapur-2001

- M. S. Sujatha (Shastri); ‘SALLEKHANA MEMORIALS OF KARNATAKA- A BREIF NOTE’; Historicity Research Journal, Volume 1, Issue 1, Sept-2014

- Justice T.K. Tukol, Sallekhana is not suicide., L.D. Institute of Indology, 1976.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJXrTqye_yc (E-SOURCE)

Ananya Jain is currently pursuing Masters of Arts in Ancient Indian History, culture and Archaeology, Panjab University, Chandigarh. She has completed her bachelor’s degree in (Honors) History from Delhi University.

As a heritage conservation, world cultures and archaeology enthusiast, she wishes to contribute in the area of field archaeology both in her hometown in Jammu & Kashmir, and around India.