Introduction

Narasimha stands as the fourth and perhaps most visually arresting avatāra of Lord Vishnu. Manifesting during the Satya Yuga, this incarnation was a specific divine response to the boon of invincibility granted to the demon king, Hiraṇyakaśipu. The demon had secured a guarantee that he could not be slain by man or beast, by day or night, inside or outside a residence, nor by any weapon known to creation. Consequently, Lord Vishnu assumed a form that defied all standard categories of existence: a liminal being who was neither fully human nor fully animal, appearing at sandhyā (twilight—neither day nor night), upon the dehali (threshold—neither inside nor outside), to disembowel the demon with his claws (which are not manufactured weapons).

In the realm of Indian art history, Narasimha represents a profound “Divine Paradox.” He is the embodiment of Raudra Rasa (fury) and Ugra (ferocity) while destroying adharma, yet simultaneously embodies Śānta Rasa (peace) and Bhakti-vatsalya (affection for the devotee) when protecting Prahlāda. While historical texts such as the Vihagendra Saṁhitā intricately classify up to 74 distinct variations (catur-saptati-mūrti) of the deity—ranging from one-faced to multi-faced and two-armed to sixteen-armed forms—temple iconography typically distills these into specific archetypes. These sculptural/iconographic depictions do not merely narrate a myth; they serve as visual scriptures, evolving from the muscular realism of Gupta-era reliefs to the intricate, lace-like ferocity of Hoysala carvings, each dynasty interpreting the “Great Protector” through their own distinct aesthetic and theological lens.

Primary Iconographic Categories: Textual and Visual Classification

While the Puranic stories describe a fluid narrative, the canonical texts of Hindu iconography—specifically the Vaikhanasa Āgama and the Vishnudharmottara Purāṇa—crystallize the deity into distinct, static forms. These texts classify Lord Narasimha not merely by his physical attributes, but by his bhāva (mood) and the specific moment of the narrative he occupies. Broadly, these depictions on temple walls fall into three major iconographic states: the Ferocious (Ugra/Sthuna-ja), the Meditative (Yoga), and the Benevolent (Lakṣmī/Bhoga).

Stambha-ja / Ugra Narasimha (The Ferocious Form)

This is the most dynamic representation, capturing the exact moment of the avatar’s emergence and the subsequent slaughter. It is colloquially known as Ugra Narasimha (Fierce Narasimha), but scripturally referred to as Stambha-ja (born of the pillar) or Vidhāraṇa (the ripping).

- The Narrative Moment: This depicts the tirobhava (destruction). The deity is often multi-armed (varying from 4 to 16 arms in text, though 8 to 10 is common in sculpture).

- Iconographic Markers:

- The Posture: Often shown in Alidha (a warrior’s stride) or seated with the demon Hiraṇyakaśipu prone across his thighs (urusthita).

- The Entrails (Antramālā): A key feature is the Antramālā—the garland of intestines. In this form, two hands (usually the middle pair) are shown ripping open the demon’s abdomen (vidhāraṇa), while another pair pulls out the intestines. In stylistic evolutions—particularly in Hoysala and Vijayanagara art—these entrails are stylised into looped, necklace-like garlands that hang around the deity’s neck, appearing like chains or jewelry rather than gore.

- Face: The mouth is open (vīruta-mukha), often showing fangs, with a flaming mane (jwala-kesha).

Yoga Narasimha (The Meditative Form)

This form represents the aftermath of the slaying of the demon, where the deity internalizes his fury to restore cosmic balance. It is a favorite in South Indian scholastic traditions (such as at Ghatikachala and Melkote).

- The Narrative Moment: After slaying the demon, Narasimha’s rage remained uncontrollable. He sat in yoga to control his own tejas (burning energy). Alternatively, this form is sometimes associated with him teaching the path of salvation to Prahlāda.

- Iconographic Markers:

- The Posture: He is seated in Utkuṭikāsana (a yogic squat with knees raised and crossed).

- The Yogapaṭṭa: The defining feature is the Yogapaṭṭa—a band of cloth tied around his back and knees to support the legs in this difficult meditative pose.

- Expression: The face is calm, often with three eyes (trinetra), and the hands rest on the knees in Yoga-mudra or Jñāna-mudra.

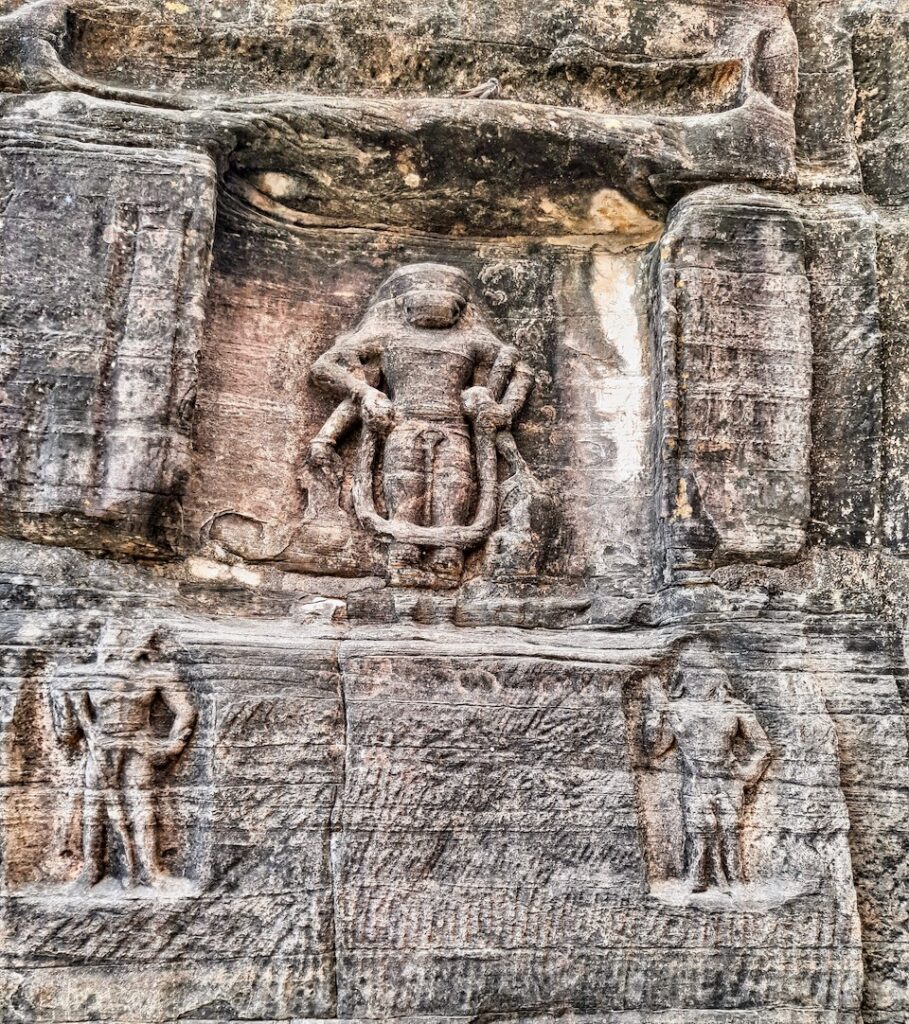

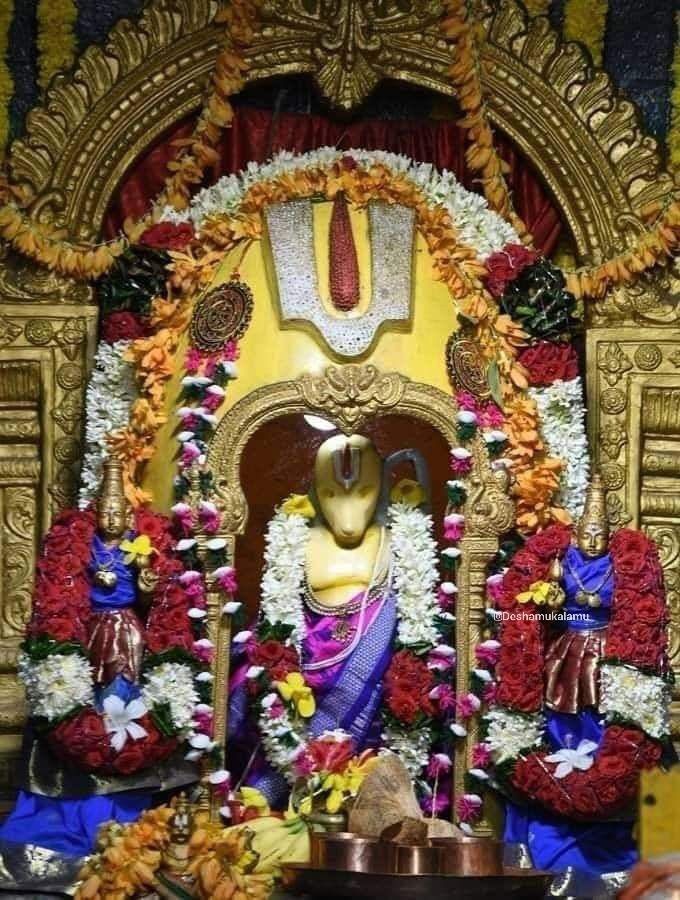

C. Kevala and Girija Narasimha (The Solitary Forms)

Kevala Narasimha refers to the “Absolute” or “Alone” form, depicted without the demon and without a consort.

- Girija Narasimha (Mountain-born) is a specific subtype of this. It depicts the deity emerging from a mountain cave rather than a man-made pillar.

- Iconographic Markers: In this solitary (Kevala) form, Lord Narasimha is depicted seated in a serene, meditative posture within a cave-like shrine. His expression is calm and introspective, symbolizing the stillness following divine fury. Unlike the fierce Ugra forms, he appears composed, with minimal ornamentation. Though traditionally described as four-armed (chaturbhuja) holding the conch (shankha) and discus (chakra), many sculptures — such as this one — depict him with simplified features, emphasizing his yogic solitude. The surrounding enclosure and the implied serpent canopy (Ādiśeṣa) represent the protective energy of spiritual withdrawal and the sacred cave of inner meditation.

D. Lakṣmī-Narasimha (The Benevolent Form)

Also known as Bhoga Narasimha (Narasimha of Enjoyment), this is the pacified form worshipped in domestic shrines and major temples to ensure prosperity.

- The Narrative Moment: The goddess Lakshmi (his consort) manifests to cool his anger, which neither the gods nor Prahlāda could fully pacify.

- Iconographic Markers:

- The Posture: Usually seated on a lotus or throne (simhasana) with the right leg hanging down (lalitasana).

- The Consort: Lakshmi is seated on his left thigh (vama-uru). His left arm embraces her waist, while she holds a lotus.

- Expression: The face is Saumya (benign), often smiling, replacing the lion’s snarl with a majestic, royal countenance.

Regional and Dynastic Variations: The Evolution of Form

The iconography of Narasimha is not monolithic; it serves as a canvas for the artistic priorities of each dynasty. While the scriptural basis remains the Puranas and Agamas, the aesthetic execution—the way the lion roars, the way the claws tear, and the ornamentation of the gore—shifts dramatically from the robust realism of the Guptas to the baroque intricacy of the Hoysalas.

(a) South India: From Grace to Grandeur

1. The Chola Dynasty (c. 9th–13th CE): The Aesthetic of Restraint In the Tamil heartland, the Chola aesthetic favored dignity over dynamism. Unlike the violent depictions of later eras, Chola Narasimhas are often characterized by a slender, sinewy physique rather than bulky muscle.

- Key Form: Mostly Kevala Narasimha (standing alone) or Yoga Narasimha.

- Stylistic Signature: The lion face is often treated with a degree of naturalism, but the body remains distinctly human and king-like. The violence is implied rather than explicit. At sites like the Amritaghateswarar Temple (Melakadambur), the deity is shown in a niche, radiating a contained power (tejas) rather than explosive motion.

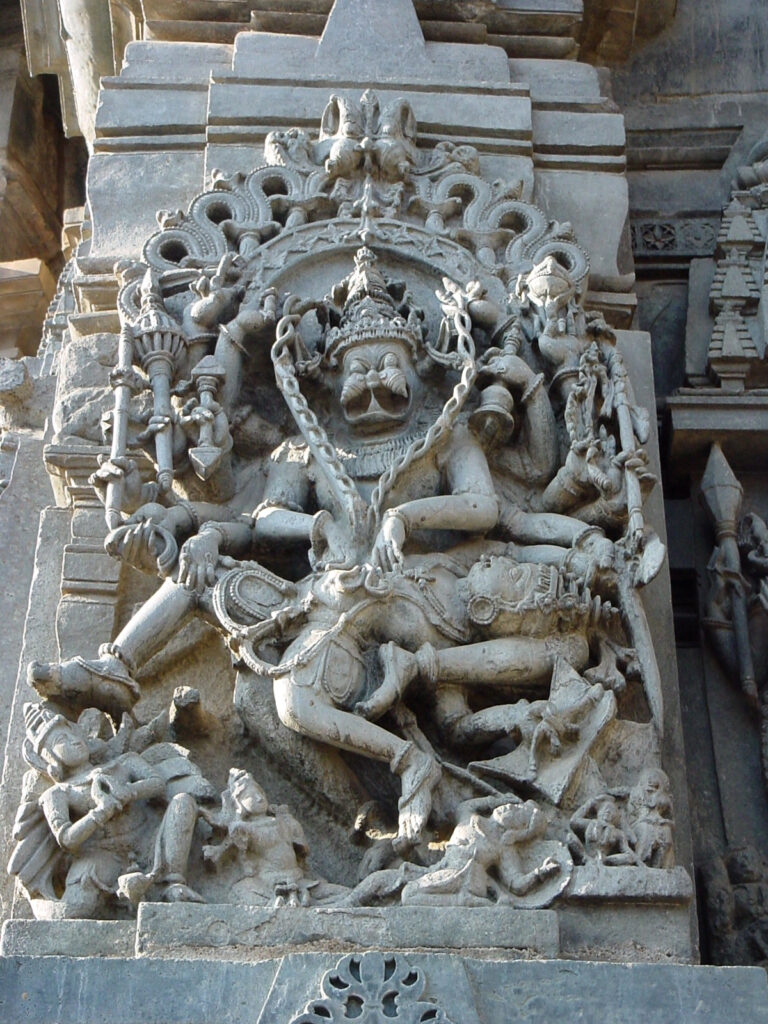

2. The Hoysala Dynasty (c. 11th–14th CE): The Baroque and the “Jeweled Entrails” This period marks the zenith of ornamental intricacy. the representation of the Antramālā (garland of intestines) undergoes a radical stylization here.

- Key Form: Stambha-ja / Ugra Narasimha.

- Stylistic Signature:

- The Chain/Intestine Motif: In temples like Belur and Halebidu, the horror of disembowelment is transformed into high art. The sculptors depicted the intestines not as gore, but as stylized, looped garlands that resemble chains or twisted ribbons. This is a prime example of Bībhatsa Rasa (the odious) being sublimated into artistic beauty.

- The Eyes and Mane: Hoysala Narasimhas feature protruding, bulbous eyes (to signify rage) and a mane depicted as stylized ringlets or flames, set against an ornate Prabhavali (arch) carved with unmatched precision.

3. The Vijayanagara Empire (c. 14th–17th CE): Martial Gigantism Rising as a shield against invasions, the Vijayanagara style is monumental, masculine, and martial.

- Key Form: Lakshmi-Narasimha (often colossal).

- Stylistic Signature: The famous monolith at Hampi (often mistaken for Ugra Narasimha because the Lakshmi image was damaged/removed) exemplifies this. The features are exaggerated: a wide, mask-like mouth, perfectly round staring eyes, and a massive chest.

(b) Central and North India:

1. The Gupta Period (c. 4th–6th CE): The Human-Lion This is the genesis of the structural iconography.

- Key Form: Kevala / Vira Narasimha.

- Stylistic Signature: At Udayagiri Cave 12, the image is elemental. The transition from man to lion is subtle. There are no multiple arms, no complex garlands of entrails—just a powerful, two-armed figure with a lion’s head, radiating sheer physical might. It captures the Vīra (heroic) sentiment rather than the Raudra (furious).

2. The Chandella Dynasty (Khajuraho): The Erotic and The Divine In the erotic/devotional landscape of Khajuraho, Narasimha is a central figure, often associated with the Vaikuntha (multi-headed Vishnu) cult.

- Key Form: Vaikuntha-Narasimha (Composite).

- Stylistic Signature: Narasimha is often depicted not just as a standalone avatar, but as the lion-face on the multi-headed Vaikuntha Vishnu images. When shown alone (as in the Lakshmana Temple niches), the sculpture is dynamic, with the body twisted in movement, reflecting the Chandella love for kinetic poses.

Iconographic Types: A Field Guide to Temple Walls

While there are theoretically 74 forms (Catur-saptati-mūrti), the vast majority of temple sculptures fall into five distinct visual categories. Below is a detailed analysis of the different iconographies of Lord Narasimha classified by posture (asana) and action (kriya).

I. Ugra / Stambha-ja Narasimha (The Ferocious Form)

This is the type that represents the Vidhāraṇa (the act of ripping).

- The Action: The deity is depicted in the heat of battle. He is often multi-armed (Ashta-bhuja or Shodasa-bhuja — 8 or 16 arms).

- Key Identifiers:

- The Posture: Often shown in Aliḍha (the archer’s warrior stance) or seated with the demon Hiraṇyakaśipu lying prone across his thighs (Urusthita).

- The “Chains” (Antramālā): The deity wears a garland that looks like twisted chains. In iconographic reality, this is the Antramālā—the demon’s intestines. The two lower hands are shown plunging into the demon’s belly, while two upper hands hold the entrails up in a loop, which sculptors (especially Hoysalas) stylized into decorative garlands.

- Weapons: He holds the Conch (Shankha) and Discus (Chakra) in the upper hands, while other hands may hold the demon’s sword and shield.

- Where to see it: Chennakesava Temple (Belur), Simhachalam (Andhra Pradesh), Dadhimati Mata Temple (Nagaur, Early Pratihara era).

II. Yoga Narasimha (The Meditative Form)

This form is strictly static and symmetrical. It represents the cooling of the divine anger (Shānta) and the teaching of spiritual knowledge.

- The Action: Narasimha is seated in deep meditation. There is no demon, no Lakshmi, and no movement.

- Key Identifiers:

- The Posture: Utkuṭikāsana. This is a specific yogic squat where the knees are raised and the legs are crossed at the ankles.

- The Strap (Yogapaṭṭa): This is the most crucial identifier. One can see a belt or band tied tightly around his knees and his back. This strap supports the legs in the difficult yogic pose.

- Hand Position: The hands usually rest on the knees (Gaja-hasta) or are in Chin-mudra (gesture of teaching).

- Where to see it: Melkote (Karnataka), Krishna Temple (Hampi).

III. Lakṣmī-Narasimha / Bhoga Narasimha (The Benevolent Form)

This is the domestic and protective form, representing grace (Anugraha).

- The Action: The deity is seated on a throne (Simhasana). The mood is romantic and royal, not violent.

- Key Identifiers:

- The Consort: Goddess Lakshmi is seated on his left thigh.

- The Embrace: Narasimha’s left arm goes around Lakshmi’s waist (alingana), while his right hand is raised in Abhaya Mudra (do not fear).

- The Eyes: Unlike the Ugra form which has round, bulging eyes, this form usually has almond-shaped, calm eyes.

- Where to see it: Belur (Hoysala), Namakkal (Rock-cut temple, Tamil Nadu).

IV. Ganda-Bherunda Narasimha

- The Narrative: When Narasimha’s anger could not be quelled, Shiva took the form of the beast Sarabha to subdue him. In response, Narasimha transformed into Ganda-Bherunda, a two-headed bird-beast of ultimate destruction, to counter Sarabha.

- Key Identifiers:

- Heads: Two bird heads (resembling eagles) facing opposite directions.

- Body: A mix of human and lion.

- The Prey: The sculpture often shows the bird holding elephants or lions in its claws and beak to demonstrate its colossal size.

- Where to see it: Ceiling of the Chennakesava Temple (Belur), Official Emblem of the Karnataka State.

V. Prahlāda-Varada Narasimha (The Blessing Form)

A rare but touching variation where the focus is on the devotee.

- The Action: Narasimha is shown blessing the boy Prahlāda.

- Key Identifiers:

- Scale: A small human figure (Prahlāda) stands near Narasimha’s leg.

- Gesture: Narasimha’s hand rests on the boy’s head (Hasta-mastaka-samyoga).

- Where to see it: Ahobilam (Lower Temple, Andhra Pradesh).

Unique and Rare Sculptures: Beyond the Standard Canon

While the Ugra and Yoga forms are ubiquitous, certain temple sites house “composite” or “tantric” variations of Narasimha. These rare sculptures often emerge from specific theological debates, sectarian rivalries, or the fusion of regional deities.

A. Varaha-Narasimha (The Dual Avatar)

Location: Simhachalam Temple, Andhra Pradesh.

This is perhaps the most unique Narasimha deity in India. It represents a theological fusion of the third avatar (Varaha the Boar) and the fourth (Narasimha the Lion).

- The Iconography: The image is Dvyatmaka (two-souled). The face is a composite: it possesses the snout of a boar but the fierce jaws of a lion. The body is human.

- The Ritual of “Cooling”: The deity is considered so intensely Ugra (ferocious/hot) that it is kept permanently covered in layers of sandalwood paste (Chandana), giving it the appearance of a Shiva Linga. The true shape of the idol is revealed only for 12 hours once a year, on the festival of Akshaya Tritiya (April/May). This is a rare instance where the iconography is hidden rather than displayed.

B. Narasimhi (The Female Shakti)

Location: Chausath Yogini Temples (Hirapur & Bhedaghat); Certain Tantric sites in Odisha and Madhya Pradesh; and many temples as part of Matrika panels.

Narasimha is one of the few avatars to have a distinct female counterpart, known as Narasimhi or Pratyangira. She is one of the Sapta-Matrikas (Seven Divine Mothers).

- The Iconography: She is depicted with the head of a lioness and the body of a woman.

- The Distinction: Unlike the male Narasimha who represents the destruction of external demons, Narasimhi is often associated with the destruction of internal enemies and esoteric protection. In the Hirapur Yogini temple (Odisha), she is shown sitting on either lion or a lotus, emphasizing her connection to wild, unbridled nature.

C. Vaikuntha Chaturmurti (The Kashmiri Composite)

Location: Martand Sun Temple ruins (Kashmir) and Lakshmana Temple (Khajuraho).

In the northern traditions (Kashmir and the Gupta realm), Narasimha often appears not as a standalone figure but as part of a four-faced Vishnu, known as Vaikuntha Chaturmurti.

- The Iconography: The central face is human (Vishnu). The right face is a Lion (Narasimha), and the left face is a Boar (Varaha). The rear face is often Kapila (the sage) or a Horse (Hayagriva).

- Significance: This sculpture encapsulates the entirety of Vishnu’s power—Knowledge (Human), Strength/Power (Lion), and Prosperity (Boar)—in a single body. It is a masterpiece of syncretic theology.

D. Jwala Narasimha

Location: Ahobilam (Upper Temple), Andhra Pradesh.

While many iconographies of Lord Narasimha show him having flaming hair, Jwala Narasimha specifically represents the deity at the exact moment of killing the demon, where his anger manifests as physical fire.

- The Iconography: This is often an eight-armed (Ashta-bhuja) form.

- Unique Feature: The sculpture is often depicted inside a rim of flames (Jwala-mala). In Ahobilam, the idol is located near a natural geographical cleft in the mountain. The sculpture here captures the rawest aspect of the deity.

Conclusion:

The iconography of Lord Narasimha stands as one of the most compelling chapters in the history of Indian art, for it challenges the sculptor to capture the impossible — a moment that exists nowhere in nature. From the restrained, humanized reliefs of the Gupta age to the dynamic, multi-armed images of the medieval Vaishnava revival and the ornate, jewel-like renderings of the Hoysala ateliers, the evolution of Narasimha imagery traces not only artistic innovation but also profound theological transformation.

For a devotee, these visual variations are never merely aesthetic. Each form embodies a distinct spiritual function. The Ugra Narasimha represents divine wrath channeled toward the protection of cosmic order — a guardian form revered by rulers and warriors.The Yoga Narasimha representing serene and composed, embodies inward control and yogic stillness, guiding seekers toward spiritual discipline. The Lakshmi Narasimha, in contrast, personifies reconciliation and grace (anugraha), restoring harmony after cosmic turbulence.

Ultimately, the image of Narasimha is a study in the Theology of the Threshold. Whether it is portrayed in the act of tearing apart the demon or in the meditative repose within a cave, the form reveals a truth that transcends polarity — that the Divine resides in the limited spaces: between man and beast, between fury and compassion, between destruction and preservation.

Jyotirmoy Dutta is a 19-year-old student at Thadomal Shahani Engineering College under Mumbai University, pursuing a degree in Artificial Intelligence and Data Science. Passionate about history, architecture, and archaeology, he is also passionate about researching the intricate details of ancient and medieval Indian temples. His deep fascination with sculptural art extends beyond research, as he actively engages in creating sculptures, blending tradition with artistic expression.

Sources and Bibliography

Primary Texts (Sanskrit):

- Vaikhanasa Āgama (Marichi Samhita): The primary source for the measurement and posture of the Yoga and Kevala forms.

- Vishnudharmottara Purāṇa (Khanda III): The standard text for Gupta and early medieval iconography.

- Silpa Ratna: A 16th-century Kerala text detailing the complex, multi-armed Tantric forms.

Secondary Sources (Art History):

- Gopinatha Rao, T.A. (1914). Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. 1, Part I & II. (The seminal work on Indian iconography).

- Champakalakshmi, R. (1981). Vaishnava Iconography in the Tamil Country. (Crucial for Chola and Pallava distinctions).

- Banerjea, J.N. (1956). The Development of Hindu Iconography. (Focuses on the evolution from coins/seals to temple walls).

- Desai, Kalpana. (1973). Iconography of Vishnu. (Excellent analysis of the Vaikuntha-Chaturmurti and Northern variants).