The Hoysala temples of Karnataka, located in the Belur, Halebidu and Somananthpura regions, made their way into the Unesco World Heritage list. The announcement was made on UNESCO’s official handle on X (formerly Twitter) on Monday 18th September. The temples, called the ‘Sacred Ensembles of the Hoysala’, have been on Unesco’s tentative list since April 2014. With this inclusion, there are 42 World Heritage Sites located in India. Out of these, 34 are cultural, 7 are natural, and one, the Khangchendzonga National Park, is of mixed type.

The splendidly beautiful temples built under Hoysala rule have always been among the most popular destinations for the archaeology and iconography enthusiast. With the inclusion in the list, we can expect the tourism to flourish even more in the region.

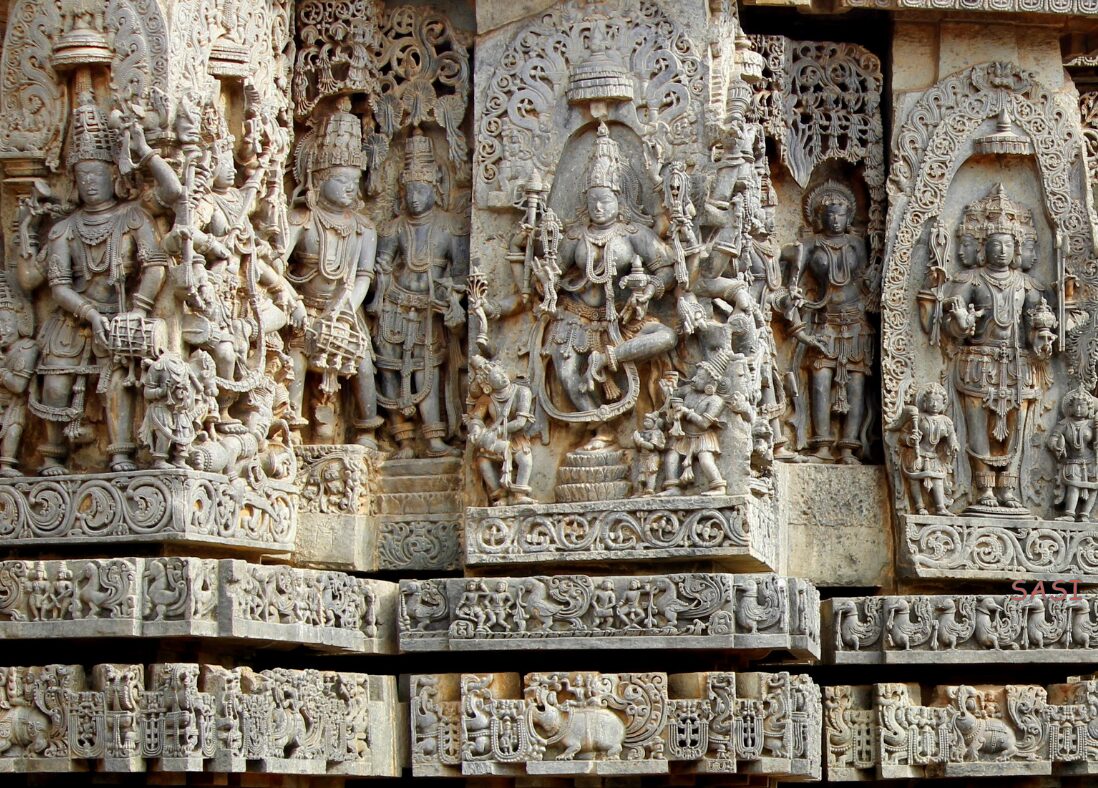

The official website of UNESCO said the shrines in the temples are characterised by hyper-real sculptures and stone carvings that cover the entire architectural surface, a circumambulatory platform, a large-scale sculptural gallery, a multi-tiered frieze, and sculptures of the Sala legend.

The Hoysala Empire was a Kannadiga power originating from the Indian subcontinent that ruled most of what is now Karnataka between the 10th and the 14th centuries. The capital of the Hoysalas was initially located at Belur, but was later moved to Halebidu.

The Hoysala era was an important period in the development of South Indian art, architecture, and religion. The empire is remembered today primarily for Hoysala architecture; 100 surviving temples are scattered across Karnataka. Among all these, the three well-known temples which exhibit an amazing display of sculptural exuberance are included in the list. The Hoysala rulers also patronised the fine arts, encouraging literature to flourish in Kannada and Sanskrit.

Hoysala influence was at its peak in the 13th century, when it dominated the Southern Deccan Plateau region. Large and small temples built during this era remain as examples of the Hoysala architectural style, including thethree temples. Other examples of Hoysala craftsmanship are the temples at Belavadi, Amruthapura, Hosaholalu, Mosale, Arasikere, Basaralu, Kikkeri and Nuggehalli. Study of the Hoysala architectural style has revealed a negligible Indo-Aryan influence while the impact of Southern Indian style is more distinct.

Temples built prior to Hoysala independence in the mid-12th century reflect significant Western Chalukya influences, while later temples retain some features salient to Western Chalukya architecture but have additional inventive decoration and ornamentation, features unique to Hoysala artisans. Some three hundred temples are known to survive in present-day Karnataka state and many more are mentioned in inscriptions, though only about seventy have been documented. The greatest concentration of these are in the Malnad (hill) districts, the native home of the Hoysala kings.

Hoysala architecture is classified as part of the Karnata Dravida tradition, a trend within Dravidian architecture in the Deccan that is distinct from the Tamil style of further south. Other terms for the tradition are Vesara, and Chalukya architecture, divided into early Badami Chalukya architecture and the Western Chalukya architecture which immediately preceded the Hoysalas. The whole tradition covers a period of about seven centuries began in the 7th century under the patronage of the Chalukya dynasty of Badami, developed further under the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta during the 9th and 10th centuries and the Western Chalukyas (or Later Chalukyas) of Basavakalyan in the 11th and 12th centuries. Its final development stage and transformation into an independent style was during the rule of the Hoysalas in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Most Hoysala temples have a plain covered entrance porch supported by circular or bell-shaped pillars which were sometimes further carved with deep fluting and moulded with decorative motifs. The temples may be built upon a platform raised by about a metre called a “jagati”. The jagati, apart from giving a raised look to the temple, serves as a pradakshinapatha. It is used for circumambulation around the temple, as the garbagriha provides no such feature.

Such temples will have an additional set of steps leading to an open mantapa (open hall) with parapet walls. A good example of this style is the Kesava Temple at Somanathapura. The jagati which is in unity with the rest of the temple follows a star-shaped design and the walls of the temple follow a zig-zag pattern, a Hoysala innovation.

The open mantapa which serves the purpose of an outer hall (outer mantapa) is a regular feature in larger Hoysala temples leading to an inner small closed mantapa and the shrines. The open mantapas which are often spacious have seating areas (asana) made of stone with the mantapa’s wall acting as a back rest.

The seats may follow the same staggered square shape of the parapet wall. The ceiling here is supported by numerous pillars that create many bays. The shape of the open mantapa is best described as staggered-square and is the style used in most Hoysala temples.

If the temple is small it will consist of only a closed mantapa (enclosed with walls extending all the way to the ceiling) and the shrine. The closed mantapa, well decorated inside and out, is larger than the vestibule connecting the shrine and the mantapa.

Hoysala artists are noted for their attention to sculptural detail be it in the depiction of themes from the Hindu epics and deities or in their use of motifs such as yali, kirtimukha, aedicula (miniature decorative towers) on pilaster, makara, hamsa, spiral foliage, animals such as lions, elephants and horses, and even general aspects of daily life such as hair styles and jewellery.

Salabhanjika, a common form of Hoysala sculpture, is an old Indian tradition going back to Buddhist sculpture. In the Hoysala idiom, madanika figures are decorative objects put at an angle on the outer walls of the temple near the roof so that worshipers circumambulating the temple can view them.

The sthamba buttalikas are pillar images that show traces of Chola art in the Chalukyan touches. Some of the artists working for the Hoysalas may have been from Chola country, a result of the expansion of the empire into Tamil-speaking regions of Southern India. The image of mohini on one of the pillars in the mantapa of the Chennakeshava temple is an example of Chola art.

General life themes are portrayed on wall panels such as the way horses were reined, the type of stirrup used, the depiction of dancers, musicians, instrumentalists, and rows of animals such as lions and elephants). Perhaps no other temple in the country depicts the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics more effectively than the Hoysaleshwara temple at Halebidu. Erotica was a subject the Hoysala artist handled with discretion. There is no exhibitionism in this, and erotic themes were carved into recesses and niches, generally miniature in form, making them inconspicuous.

Apart from these sculptures, entire sequences from the Hindu epics (commonly the Ramayana and the Mahabharata) have been sculpted as well. Depictions from mythology such as the epic hero Arjuna shooting fish, Ganesha, Surya, Indra, Brahma with Sarasvati are common.

Also frequently seen is Mahishasuramardini and Harihara (a fusion of Shiva and Vishnu) holding a conch, wheel, and trident. Many of these friezes were signed by the artisans, the first known instance of signed artwork in India.

Hindu temples began as simple shrines housing a deity and by the time of the Hoysalas had evolved into well-articulated grand structures, in which worshippers sought to go beyond the daily world and seek meaning of life. Hoysala temples were not limited to any specifically organised tradition of Hinduism and encouraged pilgrims of different Hindu devotional movements. The Hoysalas usually dedicated their temples to Shiva or to Vishnu, but they also built some temples dedicated to the Jainism as well.While King Vishnuvardhana and his descendants were Vaishnava by faith, records show that the Hoysalas maintained religious harmony by building as many temples dedicated to Shiva as they did to Vishnu.

Most of these temples have secular features with broad themes depicted in their sculptures. This can be seen in the famous Chennakesava Temple at Belur dedicated to Vishnu and in the Hoysaleswara temple at Halebidu dedicated to Shiva. The Kesava temple at Somanathapura is different in that its ornamentation is strictly Vaishnava. Generally Vaishnava temples are dedicated to Keshava (or to Chennakeshava, meaning “Beautiful Vishnu”) while a small number are dedicated to Lakshminarayana and Lakshminarasimha (Narayana and Narasimha both being Avatars, or physical manifestations, of Vishnu) with Lakshmi, consort of Vishnu, seated at his feet. Temples dedicated to Vishnu are always named after the deity.

The Shaiva temples have a Shiva linga in the shrine. The names of Shiva temples can end with the suffix eshwara meaning “Lord of”. The name “Hoysaleswara”, for instance, means “Lord of Hoysala”. The temple can also be named after the devotee who commissioned the construction of the temple, an example being the Bucesvara temple at Koravangala, named after the devotee Buci.

The Doddagaddavalli Lakshmi Devi Temple is an exception as it is dedicated to neither Vishnu nor Shiva. Hoysalas also built many Jain temples. Two notable locations of Jain worship in the Hoysala territory were Shravanabelagola and Kambadahalli. The Hoysalas built Jain temples to satisfy the needs of its Jain population, a few of which have survived in Halebidu containing icons of Jain tirthankaras. They constructed stepped wells called Pushkarni or Kalyani, the ornate tank at Hulikere being an example.

While medieval Indian artisans preferred to remain anonymous, Hoysala artisans signed their works, which has given researchers details about their lives, families, guilds, etc. Apart from the architects and sculptors, people of other guilds such as goldsmiths, ivory carvers, carpenters, and silversmiths also contributed to the completion of temples. The artisans were from diverse geographical backgrounds and included famous locals. Prolific architects included Amarashilpi Jakanachari, a native of Kaidala in Tumkur district, who also built temples for the Western Chalukyas. Ruvari Malithamma built the Kesava Temple at Somanathapura and worked on forty other monuments, including the Amruteshwara temple at Amruthapura. Malithamma specialised in ornamentation, and his works span six decades. His sculptures were typically signed in shorthand as Malli or simply Ma.

Dasoja and his son Chavana from Balligavi were the architects of Chennakesava Temple at Belur; Kedaroja was the chief architect of the Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu. Their influence is seen in other temples built by the Hoysalas as well. Names of other locals found in inscriptions are Maridamma, Baicoja, Caudaya, Nanjaya and Bama, Malloja, Nadoja, Siddoja, Masanithamma, Chameya and Rameya. Artists from Tamil country included Pallavachari and Cholavachari.

One thought on “The Divine Legacy of Hoysala Temples: An Architectural Saga”