Introduction

The Chennakeshava Temple, also known as Keshava, Kesava, or Vijayanarayana Temple of Belur, is a remarkable 12th-century Hindu temple in Belur, in the Hassan district of Karnataka, India. It is dedicated to Lord Vishnu in his attractive form of Chennakesava (meaning “handsome Kesava”). The temple stands as one of the finest works of the Hoysala Empire. King Vishnuvardhana commissioned it in 1117 CE, and it was built on the banks of the Yagachi River when Belur was a significant early capital of the Hoysalas.

The temple took 103 years to finish and developed under the support of several generations of Hoysala rulers. Over the years, it faced destruction during political conflicts and invasions. Despite this, it was rebuilt each time, showcasing its religious significance and artistic worth. Located about 35 km from Hassan and 220 km from Bengaluru, it remains an active Vaishnava temple and an important pilgrimage site.

Famous for its sculptures, friezes, inscriptions, relief panels, and overall architectural beauty, the Chennakeshava Temple tells the story of life in 12th-century Karnataka. Its artwork features scenes of dancers, musicians, court life, devotional themes, and detailed retellings of stories from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas. Although it is a Vaishnava temple, it includes elements from Shaivism, Shaktism, Jainism, and Buddhism, reflecting the religious diversity of the Hoysala period.

In 2023, the temple was included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site titled Sacred Ensembles of the Hoysalas, along with the Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu and the Keshava Temple at Somanathapura.

History

The history of the Chennakeshava Temple is closely linked to the rise and growth of the Hoysala Empire, which thrived from 1000 CE to 1346 CE. During this time, the Hoysalas constructed around 1,500 temples across nearly a thousand sites. Belur, historically known as Beluhur, Velur, or Velapura, was an early and prominent capital, renowned in inscriptions as the “earthly Vaikuntha,” or the heavenly home of Vishnu.

King Vishnuvardhana laid the foundation of the temple when he took the throne in 1110 CE. In 1117 CE, he commissioned the Vijaya-Narayana Temple (now called Chennakeshava) as one of five grand projects that marked his legacy. Scholars like M. A. Dhaky regard the temple as the king’s spiritual and artistic masterpiece, representing his political goals and his devotion to the Ramanujacharya-influenced Sri Vaishnava tradition. His queen, Santala Devi, simultaneously commissioned a smaller companion temple, the Chennigaraya Temple.

The main temple was finished and consecrated in 1117 CE, but construction continued for more than a century. After Vishnuvardhana moved his capital to Dorasamudra (now Halebidu), his successors carried on the work, culminating in the completion of temples like the famous Hoysaleswara Temple and later the Chennakesava Temple at Somanathapura.

The Hoysala period faced great challenges in the early 14th century when Malik Kafur, a general of Alauddin Khalji, invaded and looted the empire. In 1326 CE, the Delhi Sultanate invaded the region again. These attacks caused widespread destruction, damaging significant Hoysala temples like those in Belur and Halebidu.

After the Hoysala period, the temple came under the care of the Vijayanagara Empire, which repaired, rebuilt, and expanded it between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Several shrines, pillars, a new gopuram, and structural reinforcements were added during this time. In later centuries, the Mysore rulers continued to maintain the site, including repairs funded by the Wadiyar dynasty and officials during Hyder Ali’s rule.

Over 118 inscriptions, dated from 1117 CE to the 18th century, provide details about construction, grants, renovations, donations, and historical events. These inscriptions make the Chennakeshava complex one of the most well-documented temple sites in India.

Architectural & Vastu Aspects

Sacred Geometry and Hoysala Innovation

The Chennakeshava Temple at Belur showcases the best of Hoysala architecture. Here, sacred geometry, artistic skill, and ritual symbolism come together smoothly. It follows an ekakuta vimana plan, which has a single sanctum measuring about 10.5 × 10.5 meters, but the complexity of its visual and spatial design goes beyond its simple structure. The shrine combines Nagara and Dravidian architectural styles. The star-shaped ground plan and the richly decorated mouldings reflect the typical Hoysala style. The original tower, now lost, was built in the Bhumija, or curvilinear Nagara style. This fusion of regional influences highlights the artistic exchanges that flourished in the Deccan during the 12th century.

The Jagati and Ritual Movement

The whole structure sits atop a broad, three-foot-high jagati, which serves both symbolic and ritual roles. It represents the “worldly plane” that supports the divine temple above and acts as a Pradakshina Path for walking around the shrine. The jagati mirrors the star-shaped design of the temple, creating many projections that increase the sculptural surfaces. From the moment you enter through the East-facing gopuram, the gradual rise—from the ground level to the jagati, then into the navaranga hall, and finally to the inner sanctum—reflects the Vastu principle of progressing inward from the material to the spiritual world.

Vastu Alignment of Key Structures

The Chennakeshava Temple complex is one of the most well-aligned Vastu-based temple layouts in medieval India. The entire structure faces East, a direction linked to purity and good beginnings, allowing sunlight to illuminate the deity at dawn. Just past the gopuram stands the Deepa-Stambha, aligned with the main axis to symbolize the vertical channel of divine light.

In between North to Northeast direction, the most sacred direction according to Vastu, lies the impressive stepped tank known as the Kalyani or Vasudeva-Sarovar. Its placement in between the Uttara–Ishanya quadrant matches Vastu recommendations, which suggest placing water in the Northeast to boost clarity, purification, and spiritual energy. The Southeastern quadrant, linked to Agni, contains the Kalyana-Mandapa, the ceremonial pavilion for rituals, weddings, and festivals that need fire offerings. Meanwhile, the Northwestern corner has the granary, an ideal spot according to Vastu, as this direction governs movement, circulation, and storage. The entire temple complex, built of dense chloritic schist (soapstone), naturally embodies the Earth element, with its massive stone platform, load-bearing walls, and grounded geometry stabilizing and anchoring the energy field of the site. Together, these placements create a balance between the elemental forces of fire, water, air, earth, and space, making the Chennakeshava complex a model of Vastu harmony.

Shrines and Structural Layout

The entire temple complex measures about 443.5 × 396 feet and is enclosed by a fortified wall built later, entered through the Vijayanagara-era gopuram. At the center (Brahmasthan) of the campus is the main Kesava Temple, which measures 178 × 156 feet and is dedicated to Vishnu as Chennakeshava. South of this is the Kappe Chennigaraya Temple, built by Queen Santala Devi and known for its twin sanctums housing Venugopala and Chennigaraya. To the West is the elaborately carved Viranarayana Temple, featuring fifty-nine reliefs depicting figures like Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, Bhairava, Lakshmi, Parvati, and Saraswati, along with scenes from the Mahabharata. The Somyanayaki Temple lies to the Southwest and is traditionally believed to contain a small echo of the original Kesava tower. To the Northwest is the ornately decorated Andal (Ranganayaki) Temple, showcasing thirty-one sculpted deities from Vaishnava, Shaiva, and Shakta traditions. Smaller shrines dedicated to Narasimha, Rama, Krishna, Alvars, Desikar, and Ramanuja further enrich the religious landscape of the complex.

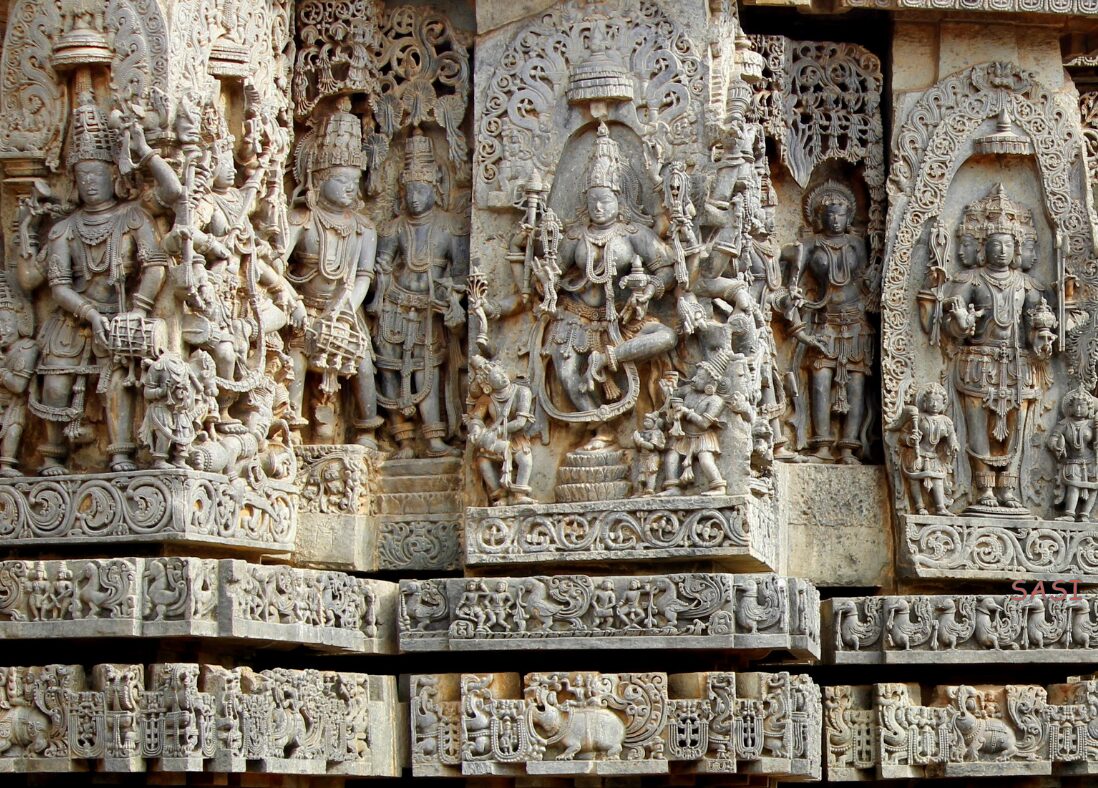

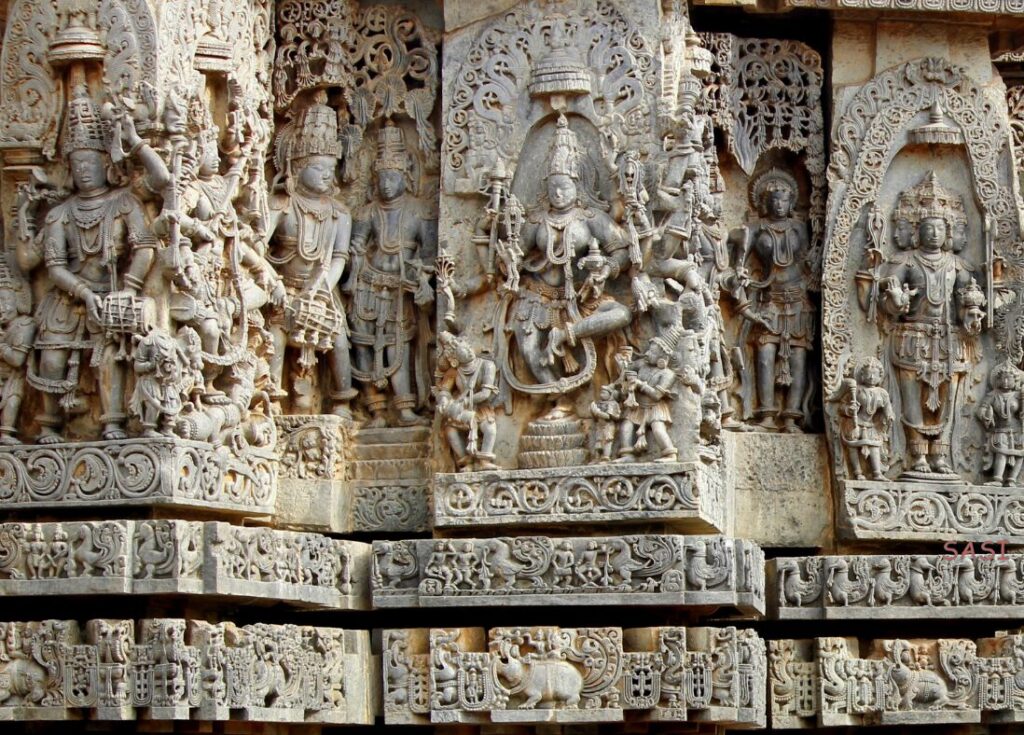

Sculptural Language and Iconographic Diversity

The outer walls of the Kesava Temple are adorned with a rich array of sculptural bands. The lowest frieze displays an extraordinary procession of 684 carved elephants, each detailed uniquely, symbolizing stability, strength, and the vastness of the cosmic foundation that supports the divine abode. Above them are panels of lions, horsemen, scrolls, dancers, musicians, and scenes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Puranas, alongside depictions of everyday life expressed through the themes of Kama, Artha, and Dharma. Higher bands feature miniature shrines, yakshas, and intricately carved creepers. Later additions introduced twenty perforated stone screens, ten telling Puranic tales and ten geometric, filtering light into the mandapa and subtly changing the atmosphere of the interior.

The temple is famous for its madanikas, or salabhanjikas—nearly forty of the original figures remain—depicting dancers, musicians, huntresses, and celestial maidens. Their expressions and body language are captured with great detail, often portraying human and divine emotions with striking realism. Some carvings show incredible miniature detail, such as a lizard stalking a fly or layered predatory scenes with animals, showcasing the sculptors’ exceptional observation skills.

Interior Craftsmanship and Sacred Spatial Drama

Inside, the navaranga mandapa, the largest of any Hoysala temple, features forty-eight pillars, each carved in a unique style. Many are lathe-turned to a smooth, polished finish. The famous Narasimha pillar is filled with miniature carvings from top to bottom, while the Mohini pillar holds eight sculptural bands depicting Vishnu’s female form next to mythological motifs. The central domed ceiling, carved like an inverted lotus, contains concentric rings narrating the Ramayana, concluding with images of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.

The sanctum houses the beautifully carved 12-foot-tall Chennakeshava murti, made from a single stone and believed in local tradition to be taller than the deity at Tirupati. The deity’s halo is carved with the Dashavatara, surrounding the supreme form with ten avatars. Belur’s tradition connects the deity with the enchanting Mohini form of Vishnu, evident in the idol’s calm posture, delicate facial features, and graceful proportions.

Materials, Artists, and Architectural Evolution

The temple was primarily carved from chloritic schist (soapstone), which allowed sculptors to produce fine, dense details while the stone was soft. As it hardened, the carvings became very durable. Many artists signed their work, revealing renowned Hoysala sculptors like Ruvari Mallitamma, Dasoja, Chavana, Malliyanna, Nagoja, Chikkahampa, and Malloja. Their craftsmanship ties Belur to the artistic line of the Western Chalukyas of Aihole, Badami, and Pattadakal.

Conclusion

Built over 113 years and later enhanced by contributions from Vijayanagara kings, Mysore patrons, and local artisans, the temple showcases centuries of architectural variety. Each phase introduced its own shrines, pillars, and structural features, creating a complex that is not uniform but beautifully layered. The Chennakeshava Temple stands today as evidence of extraordinary diversity—of dynasties, artistic traditions, building methods, devotional expressions, and the many Indian cultures and rituals that have converged here. All of these elements are woven into one continuous, living sacred landscape.