The list of kings who have enjoyed historic connections to Buddha and his creed is spread across volumes. But, in this gargantuan constellation, some names shine with incredible splendor- Aśoka and Kaṇiṣka. While one memorialized Buddha’s words and the philosophy behind it through his extensive edicts, the other immortalized the Buddha by extending unrivalled patronage to Buddhist monasteries, and representing Buddha himself on his coins and statuary, which was, by all means, not just culturally innovative, but politically radical. This unseconded act of iconicity not only created canons of Buddhist visualization, but also standardized Buddha’s depiction for eons to come. More epochal, however, was the historic relationship between Kaṇiṣka and the Buddha image, which effectively became an uncanny symbol of power and piety.

Initial steps: Commencement of Kuṣāṇa-Buddhist Intercourse

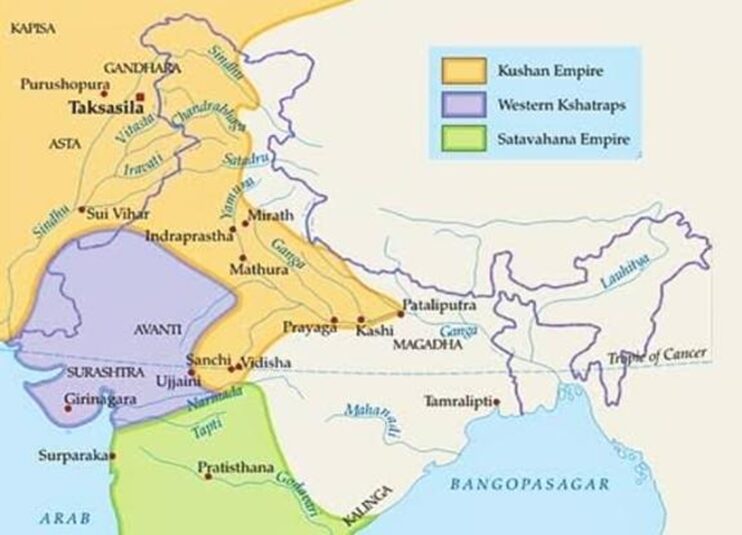

Taking over the reins of kingship from the Indo-Greeks, Kuṣāṇas attempted to create syncretism in a multicultural world. While the religious inclination of Kujula Kadphises, founder of Kushan dynasty, remains obscured, the involvement of Prince Sadkuṣāṇa/Sadakṣana in placing Buddhist relic at Taxila suggests increasing interest of Kuṣāṇa in Buddhist rituals. During the short yet impactful reign of Vima Takhto (c. 80-92 CE), Kushan boundaries reached Mathura, which created two prominent Buddhist centers in Kushan empire- Gandhāra and Mathurā. While Vima Kadphises (c. 92-127 CE) had an essentially Śaivite bent of faith (Falk 2018), his reign saw unabated extension of sponsorship to Buddhist monks and monasteries (Brancaccio 2006: 212). It was, eventually, the epochal reign of his son and successor Kaṇiṣka which brought the dawn of Buddhist efflorescence in Kushan Age.

Iconic Maturity: Buddha’s beneficence, Kaṇiṣka’s bloodlust

The historical figure of Kaṇiṣka predominates the discourse associated with royal reverence of the Buddha. In fact, Buddhist texts define him using concepts of re-births and character-transformation, traits common to the Buddhist narratives of Aśoka (Lahiri 2018), thereby placing him in a supra-natural relationship with the Buddha. Even in the travelogues of Xuanzang, Kaṇiṣka is hailed as the supreme benefactor of Buddhism in Gandhāra, contrasted with the reckless destruction of Buddhist monasteries that was unleashed later by Mihirakula (c. 515-530 CE). Kaṇiṣka not only built innumerable Buddhist structures, but promoted development of new monasteries and doctrines with indefatigable zeal, and thence gained an enviable position in Buddhist annals.

At this juncture, a seemingly interesting paradox comes to mind- legends speak of the unquenchable thirst of Kaṇiṣka for conquests, bloodsheds and annihilation of rivals, tendencies strongly un-Buddhist. Even Buddhist legends that praise him do not shy away from giving gory details of his sanguine brutality. This begs the question- how, despite Kaṇiṣka’s bloodlust, he became Buddha’s beloved. The answer ostensibly comes from the historically poignant acts of Kaṇiṣka, who not only sponsored exquisite monuments and sagacious councils on Buddhist tenets, but prominently featured and deliberately linked the Buddha image with himself, a phenomenon whose evidence is patently gleaned from four sources- coins, caskets, texts, and most importantly- the 4th Buddhist Council.

Texts

In textual legends, Kaṇiṣka is the subject of many prophecies. They not only shed light over his character, but also herald the ‘coming’ of a figure of awe, a motif that reached newer heights during Kuṣāṇa period (Salomon 2006: 140-42). Vinaya Sutra (II. 25) asserts that the Buddha prophesizes that the world-renowned Kaṇiṣka Stūpa would be built at a particular place, features of which are further elucidated in a Dunhuang Scroll-

A desire thus arose in [Kaṇiṣka to build a vast stupa]….at that time the four world-regents learnt the mind of the king. So for his sake they took the form of young boys….[and] began a Stūpa of mud….the boys said to [Kaṇiṣka] ‘We are making the Kaṇiṣka-Stūpa.’….At that time the boys changed their form….[and] said to him, ‘Great king, by you according to the Buddha’s prophecy is a Saṃghārāma to be built wholly (?) with a large Stūpa and hither relics must be invited which the meritorious good beings…will bring.”

Xuanzang further corroborates and complements the aforementioned legend-

“Kaṇiṣka became sovereign of all Jambūdvīpa (Indian subcontinent) but he did not believe in Karma, but he treated Buddhism with honor and respect as he himself converted to Buddhism intrigued by the teachings and scriptures of it. When he was hunting in the wild country a white hare appeared; the king gave a chase and the hare suddenly disappeared at [the site of the future stupa]….[when the construction of the Stūpa was not going as planned] the king lost his patience and took the matter in his own hands and started resurrecting the plans precisely, thus completing the stupas with utmost perfection and perseverance. These two stupas are still in existence and were resorted to for cures by people afflicted with diseases.”.

Śrī-dharma-piṭaka-nidāna-Sūtra (XIV. 98) narrates the story of a monk who, in order to make Kaṇiṣka repent over the consequences of his bloodshed, showed him different realms of Hell. This, in a way, resembles the famous legend of Aśoka’s Hell, where the bloodlust of Aśoka was satiated by the ineffectiveness of his horrors afore Upagupta, a Buddhist monk. Contextually though, Kaṇiṣka’s tale substantially differs from Aśoka’s tale, and reorients a classic Buddhist narrative-style to aptly accommodate bellicosity of Kaṇiṣka, thereby making him a Buddhist patron who was touched by pious fervor to worship Buddha, but not at the cost of conquests. Ironically, it was the socio-economic product of his quests that enabled him to extend hefty donations to Buddhist monasteries.

Coins

Kaṇiṣka’s rare BODO-type coins feature standing/sitting Śākyamuni and Maitreya Buddha on the reverse. The Buddha image shown here has distinct Hellenic features, alongside usual clothing of Gautama Buddha, unusually coupled with a heavy overcoat, and legs arranged sidewise, in a manner reminiscent of frontality commonly observed in Kushan sculptures. Buddha has Abhaya Mudra, with exceptionally elongated ears, distinctively marked Uṣnīṣa, and curled hairs; the last two features possibly derived from the obverse figure of Kushan king (Errington 2002), an idea that holds much symbolic significance. On copper coins, the Buddha appears with a slight leftward bend, as if creating the traditional dvibhaṅga pose, with left-hand placed at the hip, and right in Vitarka Mudra, positioned just afore his heart, strongly resembling the image of Buddha on the Bimaran casket. Maitreya Buddha, the Buddha of future, appears exclusively on copper coins, seated on what seems like to a lotus-throne.

The purpose of issuing Buddha-type is still not fully agreed upon. Cribb (1984: 11-17) classified them as commemorative coinage, issued possibly around the time of the renowned 4th Buddhist Council; while interesting, scholars disagree whether Kaṇiṣka actually organized a Buddhist council, or is it a later textual addition. Ellen Raven (2006: 213-15) believed that these coins were minted for a very long time, as visibly proven by stylistic variation. But the sudden disappearance of these coins after Kaṇiṣka suggests otherwise. That style can also vary in a short time-span has been proven in recent studies on Kushan coins (Bracey 2009). The relatively limited number of this coin-type, especially in gold, also calls for a shorter period of production.

Thus, even if the Buddha-type coins were produced in a very limited time, they played an immensely important role in linking Kaṇiṣka and his legend intimately to the Buddha image. How can we say this? Well, Śrī-dharma-piṭaka-nidāna-sūtra, the text referred to earlier, narrates a legend where, while protecting a Buddhist monastery from a serpent, Kaṇiṣka started emitting flames. This echoes the famous Śrāvastī Miracle of Buddha, where Śākyamuni performed a similar feat (DeCaroli 2015).

The Casket

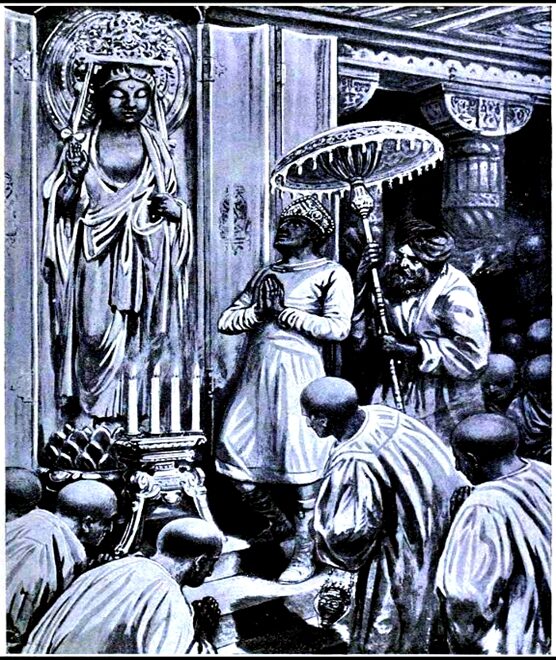

The enigmatic Kaṇiṣka reliquary casket was discovered in the 1908 excavations at Shahji-ki-dheri by D.B. Spooner. With 12.7 cm height and 18 cm diameter of the base, the casket was unearthed from the most inner chambers of the Stūpa. The casket shows four scenes: in the first, Buddha is shown seated on lotus-throne, followed by a standing Kuṣāṇa king, after which comes depiction of Buddha seated alongside Vajirapāṇi. Last scene is of Buddha with Indra and Brahma. A garland divides the narrative into different levels, with the Kuṣāṇa king placed in both realms, to highlight his metahuman status (Asher 2012).The tasteful depiction of Buddha with the powerful Kushan king further reinforces the connection between Buddha and Kaṇiṣka, a pact that was sealed for eternity in the last source to be discussed here.

The Council

The tryst of Kaṇiṣka with Buddhism reaches evidential zenith in legends connected to the 4th Buddhist Council, that was possibly instituted by Kaṇiṣka, following an advice from Thera (venerable) Pārśva. Schisms and dissensions had grown to a worrying extent inside Buddhism, which prompted Kaṇiṣka to take a definitive step towards creating harmony among disagreeing monks and scholars. According to the Sarvāstivādina tradition, the council was held at Kuṇḍalavanavihāra, whose location hitherto remains obscure. It was presided over by Vasumitra and Aśvaghoṣa. Under their vigilant watch, about 300,000 verses and nine million statements were carefully noted in written form and Sanskrit language, in order to not only preserve them, but forbid any deviation in the ways of the Buddha. Important principles of Abhidharma were inscribed on copperplates, which were later deposited inside Stūpa (probably, the Kaṇiṣka Stūpa at Puruṣapurā) by the king himself.

Opinions on the council vary- some scholars accept it after subtracting some supernatural events and omens, whole others reject it outright. David Snellgrove calls the literary tradition around the council as ‘heavily tendentious’, and the evidence as ‘not beyond rapprochement’. It is highly possible that later Buddhist texts intentionally associated the ‘legendary’ council with Kaṇiṣka to provide legitimacy to the Sarvāstivādina deviation. However, some points validate the historicity of the 4th Buddhist Council- numerous copper coins of Kaṇiṣka featuring Maitreya Buddha have been unearthed from Kashmir, which clarifies his presence in the region. The historical personalities of Vasumitra and Aśvaghoṣa can be confidently dated to c. 1st Century CE. Sanskrit did assume prominence as a court-language, a fact evident from Kushan inscriptions. Lastly, if accounts of Vasubandhu are to be believed, then Abhidharma really became a sacrosanct text of Kashmir Sarvāstivādina, atleast upto c. 5th Century CE.

Conclusion

Buddhism has often been considered as a religion that primarily operated through royal patronage. However, such a conception ignores the complex ways Buddhism and royalty mutually affected and changed each other. If Aśoka infused missionary zeal within Buddhist clergy (Olivelle 2023), Kaṇiṣka gave them commanding heights, influenced the development of Mahāyāna principles, and changed the way Buddha image was to be associated with kings. Buddha for Kaṇiṣka was not just a symbol of salvation, but a beacon of power and piety, as different sources amply demonstrate. Archaeological and literary sources set the record straight about not just Kaṇiṣka’s Buddhist bent, but his heartfelt reverence for Buddha, his philosophy, and most importantly, the Buddha’s image. In soothe, this phenomenological intertwining made both Kaṇiṣka and Buddhism un-severable from and central to each other’s legacy.

Bibliography

- Asher, Frederick. (2012). “Travels of a Reliquary, Its Contents Separated at Birth.” South Asian Studies 28, no. 2: 147-56.

- Bracey, Robert (2009). The Coinage of Vima Kadphises. Researchgate: Self published https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282293523.

- Boccaccio, P. (2006). “Gateways to the Buddha: Figures under arches in early Gandhāra Art”, pp. 210-224, In Kurt Behrendt and Pia Brancaccio (ed.) Gandhāra Buddhism: Archaeology, Art and Texts. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Cribb, Joe. (1984). The origin of the Buddha image – the numismatic evidence, in pp. 231–244. South Asian Archaeology. Cambridge, London: Cambridge University Press.

- DeCaroli, Robert. (2015). Image Problems: The Origin and Development of Buddha’s Image in Early South Asia. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Errington, Elizabeth. (2002). “Numismatic Evidence for Dating the ‘Kaniṣka’ Reliquary.” Silk Road Art and Archeology 8: 101-10.

- Falk, Harry. (2018). “Kushan Religion & Politics”. Bulletin of Asia Research Institute, Vol.29, pp.1-55.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot. (2018). Ashoka in Ancient India. New York: Harvard University Press.

- Olivelle, Patrick. (2023). Aśoka: Portraits of a Philosopher King. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers, India.

- Raven, Ellen. (2006). “Design diversity in Kaṇiṣka’s Buddha Coins”, pp. 286-302. In Kurt Behrendt and Pia Brancaccio (ed.) Gandhāra Buddhism: Archaeology, Art and Texts. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Salomon, Richard. (2006). “New Manuscript Sources for the study of Gandhāran Buddhism”, pp. 135-150. In Kurt Behrendt and Pia Brancaccio (ed.) Gandhāra Buddhism: Archaeology, Art and Texts. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Spooner, D.B. (1912). “Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī-Ḍherī.” Archeological Survey of India: Annual Report, 1908-9, pp. 38-59. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing.

Arindam Chaturvedi is an avid student of all aspects of the ancient history of India, especially its Society & Culture, Numismatics, Epigraphical records and Religious-Systems, subjects on which he has published many papers. He believes that a multifaceted field akin to our hoary antiquity requires a dynamic and all-encompassing approach, a principle which he tends to follow to the best of his abilities.