Puppetry has a significant cultural presence in India, particularly in the state of Rajasthan, where it is widely recognized as “kathputli.” The intricate handicraft involves bringing inanimate figures to life using strings and rods, skillfully manipulated by puppeteers to narrate compelling stories. While facing challenges from contemporary puppetry and technological advancements, Rajasthan’s kathputli puppetry has been conferred with a Geographical Indicator (GI) status by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

What is Puppetry?

A puppet is an inanimate object brought to life by a manipulator using strings and rods, performed in front of an audience. The word “puppet” is derived from the French word “poupee” or the Latin word “pupa,” both meaning “doll,” with the suffix “et” signifying “little.”

In the Indian Sanskrit lexicon, puppets are referred to as putraka, putrika, and puttalika, derived from the word “Putra,” meaning “son.” The puppeteer is known as a sutradhar, meaning “one who pulls strings,” a term originating from Bharata’s work “Natya Shastra” composed in the second century. A puppet’s body is not a duplicate of a human body but has its characteristics and is handled with respect. Puppets symbolize and bear stylized features.

Colours play a significant role in puppetry, with black and red representing devil-like creatures and red, yellow, and white symbolizing divine characters. Some puppets are crafted to depict deity-like beings and are coloured blue to convey their divinity and aura. Furthermore, the ornamentation, costumes, headgear, and jewellery of puppets must be intact and coordinated to present a beautiful and harmonious portrayal. The major musical instruments used during the puppetry performance are the dholak or drum, The key musical instruments utilized during puppet performances include the dholak or drum, cymbals, and chants, which are harmonized by the entire troupe, predominantly women. Off-stage sounds are produced by two wooden planks placed one on top of the other.

Puppeteers are believed to work with attentiveness and perseverance, infusing their artistry and honing their expertise. Through the ages, puppetry imparts the craft while also morally, spiritually, and historically entertaining its audience. The tradition of puppeteering is handed down from one generation to the next. Children are taught the manipulation and modification of puppets from a young age. Memorizing plays and dialogues, as well as mastering the technique of string manipulation, are crucial aspects of the profession. As puppetry is a traditional occupation passed down through generations, the bride is given a doll-shaped puppet by her father or paternal relatives.

Nowadays, puppetry is not confined to traditional practitioners, and individuals with suitable talents can pursue it. Today, we witness puppetry being pursued as a full-time vocation. Notably, when puppets reach the end of their usefulness, they are ceremoniously floated down a river with due respect and emotional gestures.

The art of puppeteering is a craft that requires attention, patience, and a touch of magic. It is a tradition passed down through generations, with children learning the skills of manipulation and performance from a young age. Memorization of scripts and mastering the technique of manipulating strings are crucial aspects of this ancient art form. While once considered a traditional profession limited to certain lineages, puppetry has evolved into a career accessible to anyone with the necessary talents.

Today, puppetry can be pursued as a full-time occupation, reflecting the changing times. Notably, when a puppet’s time has come to an end, it is given a proper and respectful farewell, often ceremoniously floated down a river with emotional reverence.

Indian History and Sources

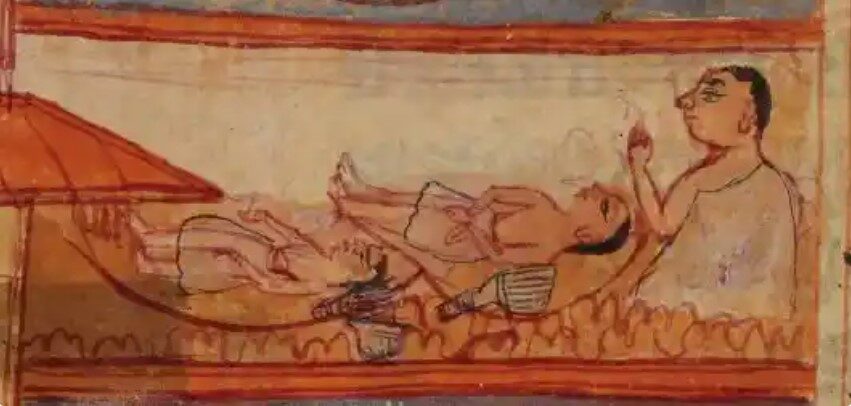

Puppetry is thought to have started in India in about the 5th century BCE. However, according to Kamala Chattopadhyay’s book Handicrafts of India, puppetry is global and has diverse origins across the world. However, records show that puppetry has only developed as an art form in India.

Historians think that the background of puppetry dates back to the Harappan Civilisation (2500 BCE) when a clay bull with a removable head attached to a thread was discovered.

Indians find the sources where puppetry has been used or played in many areas of India and many texts prove it such as Kural (Tamil Nadu). In the second century BCE, another piece of literature, the Tamil classic Silappadikaram, talks about puppetry. Puppetry is mentioned not just in Tamil writings, but also in the Mahabharata. Among the gods in Indian tradition, god is portrayed as a puppeteer in the Bhagavad Gita, manipulating the cosmos with three strings: sattva (purity and wisdom), raja (action and passion), and Tama (ignorance and inertia).

According to folklore, a carpenter creates two dolls out of wood and falls asleep. At night, Shiva and Parvati both went to the carpenter’s shop, where Parvati was awed by the dolls and asked her husband to bring them to life and dance with them. Carpenter witnessed all of this and asked the deity to repeat the scenario. Siva did, but he also advised the carpenter to do it himself. As a result, the carpenter executes his job well by making them dance with the aid of the strings. This turned out to be puppet wizardry.

What goes on behind the stage?

Step into the enchanting world of puppetry theatre, where creativity and collaboration come together to bring stories to life. The art of puppetry encompasses a wide range of productions, from educational to professional, each with its unique charm and appeal.

Let’s dive into the captivating process of script writing, which unfolds into five intriguing categories: puppet plays for children, adults, therapy, theatre, and dance-drama. Each category offers a different narrative and experience, adding depth and variety to the art form.

Vocal modulation adds another layer of enchantment to puppet performances. Every puppet has its own voice and distinctive manner of speaking, whether it’s a human, animal, or inanimate object voice, bringing characters to life in a truly magical way.

As the stage is set, puppets effortlessly come to life as they dance, moving in the air with grace and precision, accompanied by captivating music that enhances the performance. The choreography of puppet motions and dance compositions adds a unique dimension to the art of puppetry.

The magic continues with sound effects that transport both the audience and the puppets to different worlds. From thunderbolts to natural phenomena, sound effects enhance the immersive experience of puppet theatre.

Lighting plays a crucial role in setting the mood and creating a dramatic effect, guiding the audience’s focus on the puppets and their mesmerizing performances. The interplay of light and shadow adds depth and emotion to the storytelling.

At the heart of puppetry lies the art of narrative, where a puppeteer weaves captivating stories across genres, showcasing the endless possibilities of this timeless art form.

Rajasthani puppetry

Kathputli, which translates to “wooden puppet” in Hindi, is a form of puppetry that dates back to ancient times. Crafted from wood, cloth, and cotton, these puppets are brought to life using strings manipulated by skilled puppeteers. The art of kathputli was not merely a form of entertainment, but also a means of preserving and passing on Rajasthani culture and folk tales. These intricately designed puppets have been an integral part of Rajasthani performing arts, captivating audiences with their vivid portrayal of stories and traditions.

The history of kathputli is as rich and colorful as the puppets themselves. Legend has it that the Bhatts community were the pioneers behind the creation and operation of these remarkable puppets.

These puppeteers travelled from village to village, enthralling audiences with their masterful performances. Over time, kathputli evolved to encompass not only entertainment but also moral teachings and education.

The puppetry tradition suffered a decline during the Mughal invasion, but it experienced a revival during the British era when kathputlis became cherished as keepsakes. Today, these magnificent puppets can be found adorning homes and cultural showcases across Rajasthan, a testament to their enduring legacy.

The kathputlis themselves are a sight to behold, with their slender bodies, expressive features, and vibrant traditional attire. Their movements are graceful and free, captivating audiences with their lifelike portrayals of people and animals. The puppeteers, adorned with ghungrus on their wrists, skillfully bring the puppets to life, accompanied by the rhythmic beats of the dholak and the melodious whistling sounds emitted by the puppets.

However, the art of kathputli is not without its challenges.

The traditional vegetable colours used to adorn the puppets are gradually being replaced by chemically generated hues, threatening the authenticity of this age-old art form. Despite these challenges, the allure of kathputli continues to captivate audiences, keeping alive the traditions and stories of Rajasthan for generations to come.

“Precautions must be taken when constructing the set for the kathputlis, as they are manipulated using strings. It is important to avoid sharp corners, as they can cause the threads to become tangled. Sufficient space should be maintained between the puppets to allow them to move freely without getting entwined.”

“India has been granted a total of 365 Geographical Indication (GI) tags. GI tags are names registered with the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) for specific products, handicrafts, and cultural practices that are uniquely associated with a particular region, area, state, or country.”

“Rajasthan, India has received 14 of these tags. Notably, kathputli from Rajasthan was registered with application number 68 under the category of handicrafts around 2008-2009. Additionally, the puppetry logo was registered with the number 541 in 2016-17.”

Making of puppetry

The puppets are typically crafted from wood or, in some cases, a more pliable material. When using wood, screw eyes that face in opposite directions are utilized to fasten the control strings at the sides of the head and the base of the neck. For pliable materials, a wire is threaded from one ear to the other, with a loop at each end, and another wire is passed through the neck with a twisted loop connected to the first wire. While the chest is made from a single piece of fabric, the shoulders and hips consist of different materials. A central area is carved out and filled with loose materials. Puppets cannot stand on their own. The primary and essential component of puppetry is flexible joints, typically made from a malleable substance.

Manipulation

The technique of manipulating strings in kathputli is distinctive and intricate. A pair of head strings, connected to a single triangular control, are used to operate the puppets. The manipulation involves the movement of the strings by the puppeteer’s hands and fingers.

The mastery of handling and manipulating strings represents one of the most demanding aspects of puppetry. It begins with practising the sequential pulling of individual threads while standing on a chair or table. This exercise progresses from fingers to wrists and finally to hands. To ensure effective manipulation, the puppeteer should stand at least one foot above the puppet’s performance level, allowing for better control across the performance area.

Additionally, the puppet’s legs should be sturdy to maintain an upright position, and after use, the puppet should be hung on a peg with all the strings collectively wrapped around the control to prevent them from dangling.

The primary role of a puppeteer is to orchestrate the physical movements of the puppet, breathing life into it via a ring placed over the head. Simultaneously, the puppeteer generates a variety of sounds, including vocal speech and music, to enhance the puppet’s character. Puppeteers remain concealed behind a 3.5 to 4-foot-high curtain during performances.

String manipulation can be single or multiple, depending on the operator. For instance, a single puppet necessitates single-handed control, while controlling multiple puppets requires sufficient dexterity to manipulate numerous strings. Puppets can be manipulated both horizontally and vertically, with the horizontal method being more prevalent. Human figures are typically oriented vertically and feature strings attached to their heads, shoulders, legs, and hands, as well as a string at the back. Animal figurines have strings fastened around their shoulders, heads, tails, and legs, with two additional strings secured to the waist of dancing figures to facilitate dance movements with subtle gestures.

During stage performances, the puppeteer moves the kathputli from the upper to the lower level. If the performance takes place during the day, it is advisable to use a foldable stage. Thick curtains are essential to block out external light, with black fabric or curtains being preferred. Additionally, improvising a puppet stage can be achieved by utilizing a table, cot, or two seats with a curtain hung at the entrance, or even a hospital bed. This concept is commonly referred to as an improvised stage.

Characters

One group consists of 80-90 puppets portraying various characters. Anarkali, the dancer puppet, is intricately designed with numerous strings. Additionally, her limbs are sewn in a way that manipulates one side of her body creating a range of dance movements. Other notable figures with complex movements include The Horse Rider, Nimbuwala, and the Juggler. The snake charmer, identifiable by his wooden head and fabric body, is noticeably smaller than the snake. Khabar Khan, the announcer, is equipped with a drum fastened to his legs and a stick in each hand.

Narrative

The plays are depicted in the historical accounts and local legends. One such example is Amar Singh Rathore, a monarch from Nagaur known for his love for Rajasthani puppetry. Traditionally, performances of the narrative of Amar Singh Rathore, a courageous Rajput nobleman at Shah Jahan’s court, would take place in the mohallas or neighbourhoods to encourage audience participation. The show also addresses social issues such as dowry, illiteracy, poverty, and unemployment. The puppet performances cover a wide range of topics, including stories without words, myths, animal and nature stories, folklore, fairy tales, moral stories, behavioural stories, ghost stories, and even science fiction.

In a demonstration of storytelling without words, the author recreates the story of the snake and the snake chamber. This includes three snakes and a snake charmer’s flute, along with three bamboo baskets. Throughout the narrative, the snake charmer plays music for two snakes at a time, prompting them to dance and sometimes bite the swaying flute. As the story progresses, a third snake enters, leading to new patterns of pursuing, coiling, and uncoiling. The flute stops, and all three snakes gently coil back into their bamboo baskets.

Challenges faced and its future

The traditional puppet theatre has been deeply intertwined with the religious and social fabric of rural India. It has historically captured the interest of people from diverse backgrounds and has been influenced by factors such as socio-political structures, religious beliefs, and the preferences of the patron class, resulting in regional variations in themes and styles. Despite the challenges, puppet theatre has demonstrated remarkable resilience over time.

In the past, puppet making was primarily the domain of the bhattas communities, whose craftsmanship added value to the puppets and provided a source of income. However, with the rise of mass production, the traditional art of puppet making has faced a decline, with wood’s susceptibility to moisture halting production for extended periods. This has led to individuals seeking alternative sources of livelihood during these periods. Additionally, there has been a shift in the perception of puppets from a traditional art form to decorative items, diminishing the true essence of puppetry theatre. This change has impacted the livelihoods, demand, and traditions associated with puppetry, leading practitioners to seek alternative occupations.

The evolution of traditional puppetry has been shaped by changing trends in colour palettes, materials, narratives, performance styles, and spatial considerations. Contemporary puppetry has adopted modern techniques, including advancements in technology such as projections, lighting, stage sets, music, and media.

The fusion of technology and puppetry has given rise to a new genre known as animatronics. While these developments offer advantages, they also bring about challenges, and both traditional and contemporary puppetry forms are expected to fulfil their respective roles effectively.

In his essay “Specialist Voice,” Dadi Pudumjee emphasizes that puppetry should be viewed as a valuable form of communication on par with other art forms, rather than merely a prop. However, despite its cultural significance, puppetry is often relegated to a lower status in both public and private organizations, alongside other traditional art forms. Pudumjee advocates for the dignified treatment and preservation of traditional puppetry as an art form in its own right.

Conclusion

The origin of the fascination has been a great source of inspiration for my reading. Rajasthani puppetry, known as Kathputli, is a wonderful example of regional popular culture art. It not only represents a part of cultural heritage but also conveys the essence of the socio-cultural environment through its creation process. However, the most captivating aspect of this puppetry is the storytelling. This artistic process beautifully captures how puppetry combines entertainment and awareness. Moreover, the individuals involved in this art form have a long-standing connection to it, spanning numerous generations. Despite its ancient roots, this form of art has evolved and continues to thrive in the modern era with new adaptations being made by each generation.

A passionate historian in training and art enthusiast, Khushali Jain is currently embarking on her Master’s journey in the history of art at the Indian Institute of Heritage (formerly known as the National Museum Institute). She has done her bachelor’s in history with honours from Gargi College, University of Delhi. Khushali has also actively engaged with esteemed organisations like Intach and a National Museum Exhibition titled Chitram Vastram, channelling her knowledge and expertise into meaningful projects. Additionally, She has experience with heritage-guided tours for school children.