As a culture and heritage influencer, I have atleast 50 places marked as “To be visited”. But none of them had created such curiosity and excitement in me, as the Gudimallam temple. Ever since I had heard about this temple for the first time, and saw the photo of Gudimallam Linga, I was drawn to the mysterious and enigmatic Linga. When we were planning a trip to Srisailam, Pondicherry and Tirupati; I made it a point to include Gudimallam in the plan.

Introduction

A few km away from famous pilgrimage spot of Tirupati, nested by hills and a small village of Gudimallam, along a narrow road, is a temple of Sri Parasurameswara. The temple may look small to the eyes of visitor, but the temple is home to history of centuries. A history and tradition that has no parallels.

The Gudimallam Temple, in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, is renowned for its extraordinary antiquity and unique Shiva Lingam carved with human features. Located in Gudimallam village near Tirupati, this small shrine – formally known as the Parasurameswara Swamy Temple – is among the oldest Shiva temples in India still in worship. It has a rich history spanning over two millennia, with multiple phases of construction and patronage.

Temple Architecture and Plan

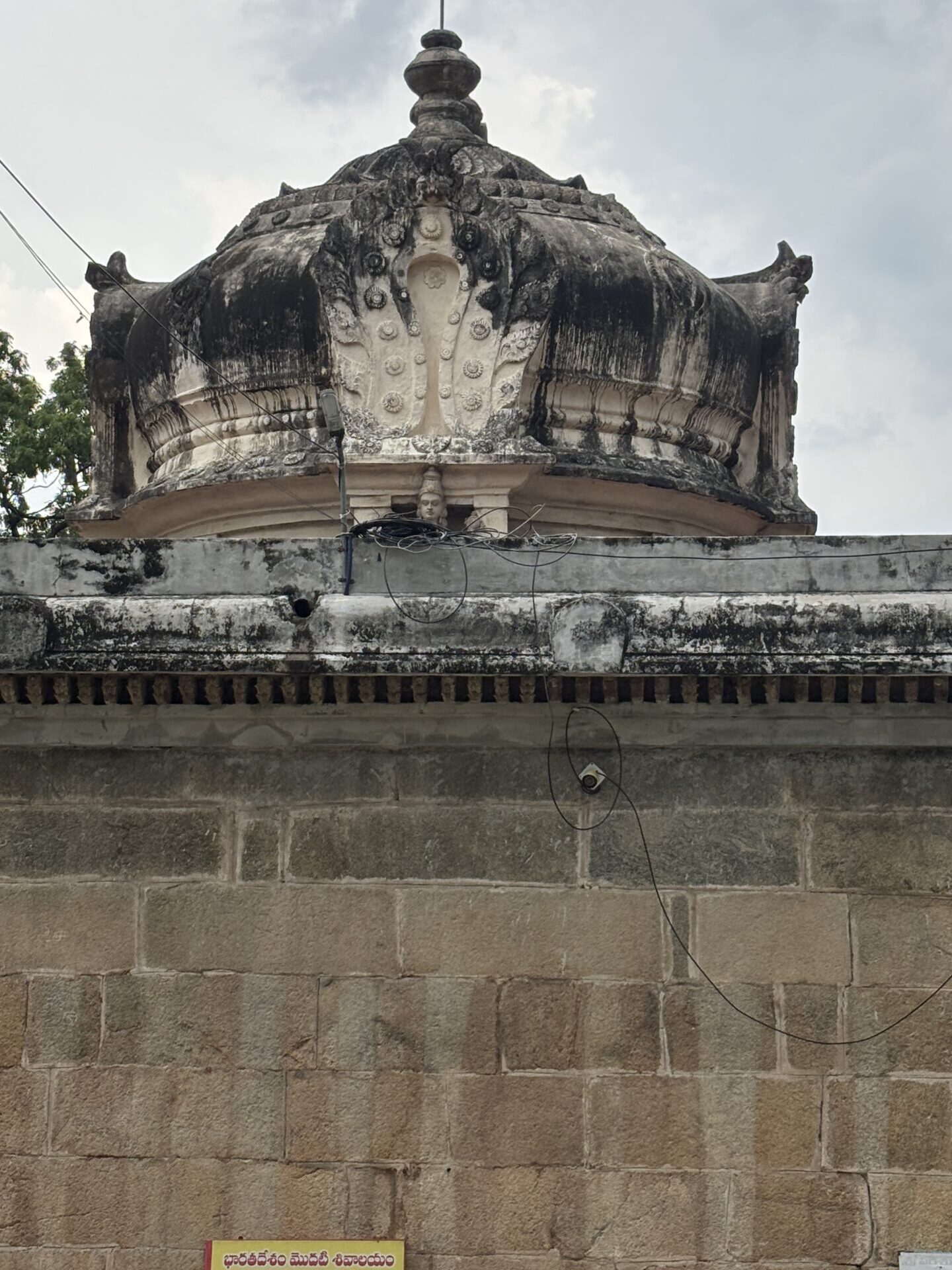

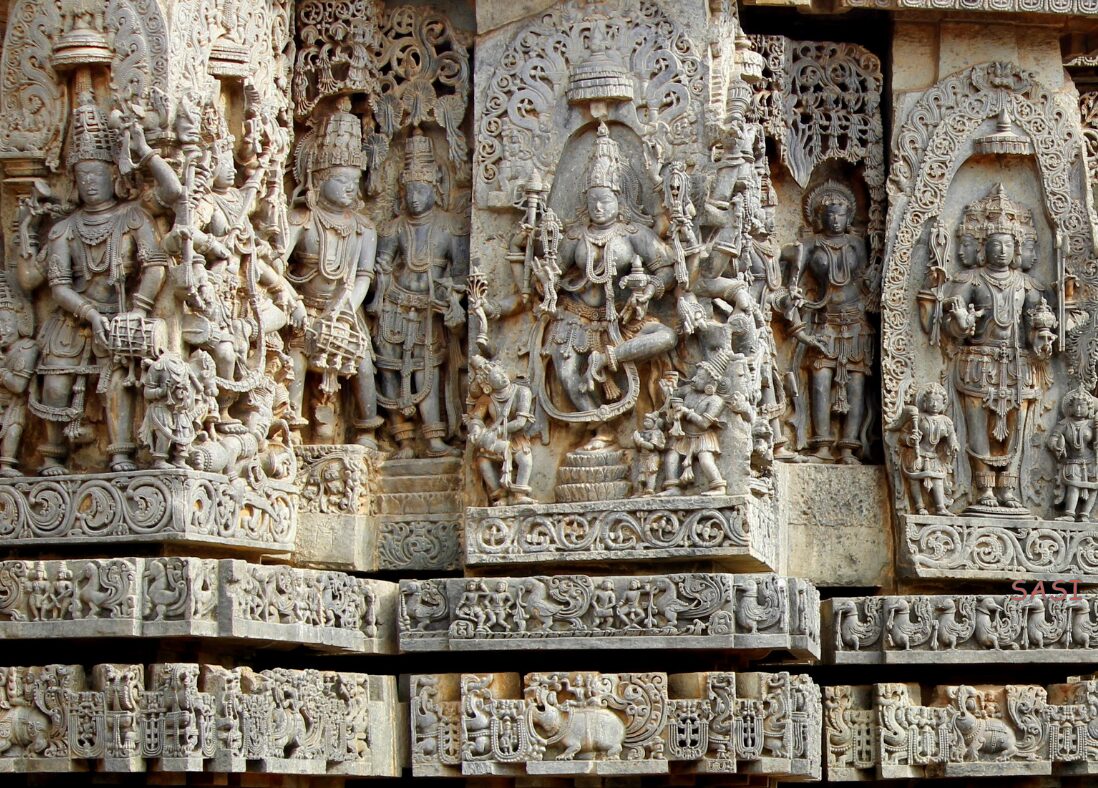

When we reached the place, with the help of google maps, we were hoping to be welcomed by a moderate to big shrine. But we could not even realise that we have reached the temple, until google lady told us “You have arrived at your destination”. With a linga that is over 5 ft in height, I was expecting a big and grand temple to exist there. Instead, the temple is very small, simple and unique. Its uniqueness is in the fact that the temple is follows an apsidal structure plan. Apsidal structure represents early phase of stand alone temple building, an important step in the evolution of temple building, that started from the cave temples and evolved further in stand alone temples with square Garbhagriha. Another apsidal structures that can be seen are the Trivikrama temple at Ter in Maharashtra, and Kapoteshwara temple at Chhejarla in Andhra Pradesh. The other two mentioned, as purely apsidal in nature, whereas the temple at Gudimallam is a mix of Apsidal and later day Dravida style. The temple roof consists of some Kudus (Decorative arched window type element) on top of the apsidal structure. This shows us an important step in the development of temple architecture, from early day plain apsidal structures to later day more decorated temples.

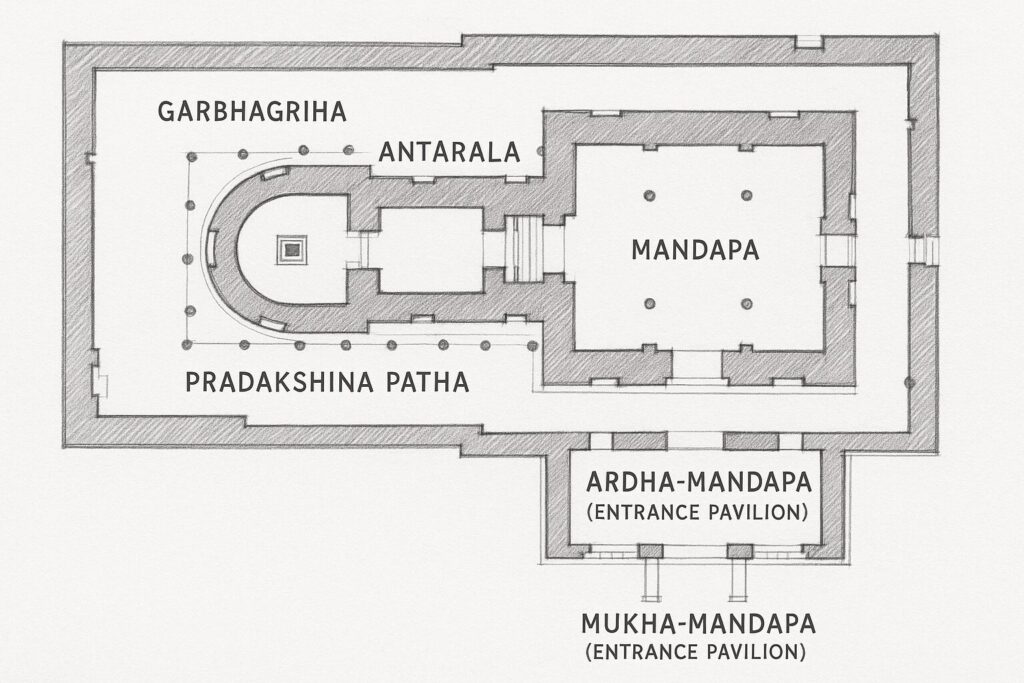

The temples follows a very simple plan. A Garbhagriha (sanctum) that houses the Lingam; connected to Maha Mandapa (pavilion) through a small Antarala (Vestibule). The Maha Mandapa is connected to outside world through an Ardha Mandapa (small pavilion) and Mukha-Mandapa (entrance pavilion). A Pradakshina (circumambulation) path is created between the temple structure and wall outside.

The architectural style is of the Dravidian order, in line with Chola-period temple aesthetics, though on a much humbler scale than the giant Chola temples of Tamil Nadu. The temple’s tower and walls are made of carved stone blocks (local Tirupati khandolite granite), and any decorative elements would be characteristic of Chola workmanship. However, since the temple is small, the ornamentation on the outer walls is minimal compared to later grand temples. The sanctum’s stone exterior is mostly plain or with simple pilasters, focusing attention on the deity inside.

Uniquely, beneath this Chola-era stone temple lie the remnants of earlier constructions. Archaeologists discovered traces of the brick temple (2nd–3rd century CE) underneath the current floor level. This earlier temple had an apsidal (rounded-end) plan, a feature discernible from the curving alignment of the brick foundation that was excavated. A section of an old lime-plastered floor from that era was also found, indicating the flooring that once surrounded the linga’s ancient railing structure. These hidden architectural layers show that the Gudimallam shrine progressed from a vedi (open altar) to an enclosed brick shrine, and finally to the present stone temple.

Origins and Historical Background

The earliest inscriptions discovered at Gudimallam date from the mid-9th century CE, during the late Pallava period. An inscription from the reign of a Pallava king, Vijayadantivikrama Varman (c. 845 CE), records donations to the temple. This shows that by Pallava times the shrine was recognized and supported by royal authority. In fact, multiple 9th–10th century inscriptions (up to about 989 CE) on the temple’s walls mention gifts and endowments to the deity, indicating continuous worship and perhaps minor additions to the temple complex under Pallava and later rulers.

The most significant inscription is from the reign of Vikrama Chola (12th century) noting the complete reconstruction of the temple in stone in 1127 CE. This inscription likely appears on a stone slab or wall of the temple and essentially credits the Chola king with rebuilding the shrine. It underscores the importance accorded to the site by the Cholas, who were great temple-builders.

Some inscriptions from after the Chola era (perhaps under the Vijayanagara empire or local chiefs) are also present, with one record as late as 1801 CE. An early 19th-century inscription is quite unusual for a temple, but it might mark a renovation or donation in that year (possibly by a local zamindar or official). The existence of this late inscription demonstrates the continuity of worship and also provides a terminus for documented patronage.

The name of the temple is mentioned as Parasurameswara Temple in the inscriptions. These inscriptions do not refer to the original builders of the temple. But they register the gifts made to the temple like land, money and cows for the conduct of daily worship in the temple. Some of the copper coins obtained at Ujjain and belonging to the 3rd century BC contain figures which resemble the Linga of Gudimallam. A 1st century sculpture in the Mathura Museum also contains a figure resembling the Gudimallam Shiva.

Though the records from stone inscriptions are available from 9th century onwards, the temple structure tells us a tale of significance of the temple in the times before that. The apsidal style (हस्तीपृष्ठ) reflects influences from Buddhist chaitya (prayer hall) architecture of that era; and can be seen at few of the earliest stand alone temples, mostly from 4th century. The brick apsidal temple tells us that the temple is existent from atleast the 4th century.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the site of Gudimallam was a place of Shaiva worship as early as the 2nd century BCE. Excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) have revealed that the temple stands on a mound containing artefacts from the early historic period (e.g. Black-and-Red Ware pottery and even a punch-marked coin). These findings suggest an initial open-air shrine: the Shiva linga was likely installed on a circular yoni-pitha (pedestal) and open to the sky, surrounded by a square railing in the ancient fashion. This primitive setup – a linga with a railing – is reminiscent of early Buddhist sacred architecture (such as the railings around ancient stupas at Bharhut and Amaravati) and underscores the shrine’s great antiquity.

About the Gudimallam Linga

The linga and temple were comparatively unknown, until the beginning of the 20th century. In 1911, T. A. Gopinath Rao, then working for Travancore Archaeology Department, first time surveyed and published a paper about the Gudimallam temple. And the temple caught eye of the researchers and devotees. Initially, the Linga was also said to be from the same time, as the temple. But the researchers had varied views about this point. The linga is unlike any other Shiva sculpture, or linga from the 5th century, or later. This lingam is about 1.5 meters in height (approximately), carved from a polished brownish sandstone, and is unique in that it bears a carved human figure in high relief on its front face. Such anthropomorphic representation on a lingam is exceedingly rare, making it the centerpiece of scholarly interest.

The figure on the lingam is widely identified as Lord Shiva in an early form. It is a full-standing male figure about half the height of the linga. The deity is depicted standing in tribhanga pose (a slight thrice-bent posture) upon a small crouching dwarf. The dwarf beneath Shiva’s feet – characterized by stout, elephant-like legs and a shrunken body – is interpreted as Apasmara, the mythical demon of ignorance who is often shown under Shiva’s feet to symbolize enlightenment triumphing over ignorance. This motif of standing on a dwarf connects the Gudimallam image to later iconography of Shiva as Nataraja (who also dances on Apasmara), albeit in a much simpler, archaic form here.

Shiva in the Gudimallam lingam has two arms (as opposed to the multi-armed forms that became common in later centuries). In his right hand, he holds a ram by its hind legs, lifting the animal upside-down. This unusual attribute has been interpreted by scholars as symbolizing Shiva in his Bhikshatana aspect – i.e., as the cosmic mendicant or beggar. In classical Shaivite lore, Bhikshatana Shiva carries a deer’s carcass or a small animal and wanders seeking alms; the ram in hand at Gudimallam is seen as an early representation of that motif.

Shiva’s left hand in the carving is less clearly preserved in accounts, but some sources suggest it might be resting on the dwarf or on his hip, and possibly holding a small vessel or axe. The temple’s traditional name “Parasurameswara” implies a connection to a Parasu (battle-axe), which hints that originally the figure may have held a battle axe in one hand – a common attribute of Shiva (as Khadga or Parashu) – or that the temple is linked to the legend of Parashurama (the axe-wielding avatar of Vishnu) worshipping Shiva. However, the carving itself currently shows the ram clearly, while an axe is not prominently visible, leading some to theorize the figure could also represent a local chieftain or devotee. The consensus, though, leans strongly towards it being an early depiction of Shiva himself.

The facial features and posture of the carved figure are also telling. Shiva’s gaze is directed downward with the eyes focusing on the tip of his nose. This detail is interpreted as a yogic trait – it resembles the meditative pose of Shiva as Yoga-Dakshinamurti (the ascetic teacher), who is often shown with introspective downward gaze. The combination of the yogic posture and the Bhikshatana ram suggests that the sculptor was merging multiple aspects of Shiva into a single form, centuries before such composite iconography was codified in Hindu art. Notably, the figure lacks many later symbols of Shiva: there is no trident, no snake around the neck, no third eye depicted – reflecting an archaic form before these iconographic conventions fully developed. He is shown with minimal ornamentation: perhaps wearing a simple loincloth and a turban-like hairdo (as the sculpture’s detail indicates a hairstyle rather than elaborate matted locks). The styling of the figure’s jewelry and the form of the dwarf have been noted as similar to motifs in 2nd–1st century BCE Sunga-period art, reinforcing the likelihood of an early date.

Significance and uniqueness

The Gudimallam lingam’s iconography is immensely significant for the study of Hindu art and religion. It represents a transitional phase where an aniconic form (the phallic lingam) is combined with an anthropomorphic representation of the deity. This might illustrate the gradual shift in worship practices – from worshipping Shiva as an abstract symbol (linga) to worshipping Shiva in human form.

Moreover, the presence of features like the yoni-pitha and surrounding railing (discovered during excavations) shows that even in the early centuries BCE/CE, the cult of the Shiva lingam had already adopted architectural symbolism similar to other contemporary religions. The ASI excavation led by K. Kutumba Sastri and K. K. Sharma uncovered the original circular pedestal (yoni) into which the lingam was fixed. This discovery corrected earlier assumptions that early lingams had no pedestals – clearly, the Gudimallam lingam was ritually installed with a proper base from the start. It also had a stone railing enclosure around it, a feature that would disappear in later Hindu temple practice but is here a snapshot of ancient ritual design.

Today, the Gudimallam Shiva lingam is still worshipped with daily rites, just as it has been for at least 2,000 years. Devotees consider it a powerful manifestation of Shiva, often referring to it as Parasurameswara. The continued veneration in situ makes it likely the oldest continuously worshipped Shiva linga in the world. For historians and pilgrims alike, standing before this lingam is a moment of connecting with a very ancient form of devotion – one that has survived invasions, the elements, and the passage of time.

Gudimallam’s core (the Shiva lingam and earliest shrine) significantly predates most other temples in South India. While famous Shaivite temples like Srisailam Mallikarjuna or Daksharama in Andhra have legendary origins, their existing structures date to the medieval or later periods. In contrast, the Gudimallam lingam originates possibly around the 3rd century BCE, and even the brick structural temple around it dates to the 2nd–3rd century CE. This makes Gudimallam several centuries older than the earliest surviving structural temples of the region. For example, the Pallava temples of nearby Tamil Nadu (like the shore temples of Mahabalipuram, 7th century CE) and the early Chalukyan temples in Telangana/Andhra (like the Alampur Navabrahma temples, 7th century CE) are roughly 500–800 years junior to Gudimallam’s first phase. In fact, art historians note that virtually no significant stone sculptures from South India before the 5th–6th century have survived apart from the Gudimallam lingam. This singular status as a pre-Pallava artifact has led to Gudimallam being a key reference point in the study of early Indian art.

Unlike some ancient sites which were abandoned, Gudimallam shows a continuous evolution through time. It started as a small rural shrine and gradually transformed into a temple complex with contributions from different dynasties. Other early Hindu temples in Andhra often do not show such long stratification. Gudimallam physically encapsulates layers from pre-Christian era to medieval era within one site. It is thus an invaluable case study of how temple architecture and religious practice developed on one spot through ages.

Another thing that sets Gudimallam apart is the incorporation of an apsidal plan in its early phase, which is very unusual for later-period Hindu temples in South India (they predominantly use square sanctums). This apsidal feature places Gudimallam in company with a few other rare early temples – such as some early Gupta-era temples in North India or certain cave temples – rather than with the later South Indian canonical styles.

When comparing the iconography, Gudimallam’s anthropomorphic linga is virtually one-of-a-kind in South India. Other ancient Shiva temples typically have separate murti (idol) of Shiva (like Nataraja or Lingodbhava) alongside a plain lingam, but none has a main lingam with Shiva carved onto it of such antiquity. A somewhat parallel concept can be found in a few early artifacts: for instance, a 1st-century CE sculpture from Mathura (North India) shows a Shiva-like figure on a pillar, and some Kushan-era coins depict Shiva with a linga – indicating that the idea of merging the icon and symbol did exist. However, those were not in an active temple context and are geographically distant. In the Andhra/Karnataka/Tamil region, the earliest substantive Shiva icons are from the 5th–6th century CE (e.g., Shiva reliefs in the Udayagiri Caves, 5th century, or Badami cave temples, 6th century). By that time, the iconography of Shiva had evolved to include multiple arms, weapons like the trident, etc. Gudimallam’s two-armed, simple form is much more archaic, aligning with a formative stage of Hindu iconography. This makes it stand out starkly when placed against other temple icons in the region, which mostly belong to the fully developed iconographic canon of the later Gupta and post-Gupta age.

Well sourced & Beautifully written . I was searching for info on Gudimallam linga as I am planning to visit the place. Dr Dinesh Soni’s article has added more awe & understanding to the idol. I will now go with the reverence & respect this ancient relic/deity/ lingam deserves. Thank you 🙏

Thank you for your appreciative words. I hope you have a positive experience there. Do remember to not go with empty stomach, or to carry food with you. you won’t get much options around the temple.