Introduction

The Lakshman Temple was constructed in the 10th century CE under the patronage of the Chandelas king Yashovarman. It is believed that Yashovarman was also known by the name Lakshman, from which the temple derives its nomenclature. The presiding deity of the temple is Lord Vishnu in his Vaikuntha form. The temple is situated at Khajuraho, a village located in the Chhatarpur district of present-day Madhya Pradesh.

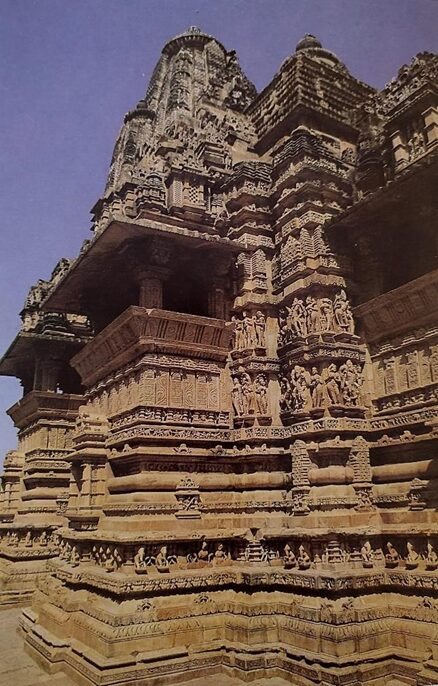

Construction of the Lakshman Temple began around 950 CE during the reign of Yashovarman and was completed in 954 CE by his son and successor, King Dhanga. Within the chronological sequence of the Khajuraho temples, the Lakshman Temple occupies the seventh position and is regarded as one of the earliest mature examples of Chandelas temple architecture. Architecturally, the temples of Khajuraho belong to the North Indian Nagara style. The Chandelas displayed a profound interest in art and architecture, which found expression in their temple-building activities. In the Lakshman Temple, the Nagara style is manifested through a high curvilinear shikhara, multiple stepped platforms, and a distinct arrangement of the mandapa and maha-mandapa, both crowned with towering superstructures. The temple also features balconies, an ambulatory passage, intricately carved interior columns, and richly ornamented wall surfaces.

The sculptural program of the temple is extensive and varied, depicting deities with multiple arms, dynamic bodily postures, refined facial expressions, and a range of erotic and amorous scenes. These sculptural elements reflect both aesthetic refinement and symbolic meaning within the broader religious context.

The construction of such a monumental structure required advanced building techniques, skilled artisans, and the use of durable materials. Locally available granite was employed for the foundation, while sandstone—laid without mortar—was used for the outer walls and superstructure. Ashlar masonry was adopted for the roofing system. Although several architects, masons, and sculptors are known to historians, the temple was not conceived as the work of an individual designer. Instead, it followed an established architectural canon, with standardised ground plans and sculptural schemes common to Chandelas temples.

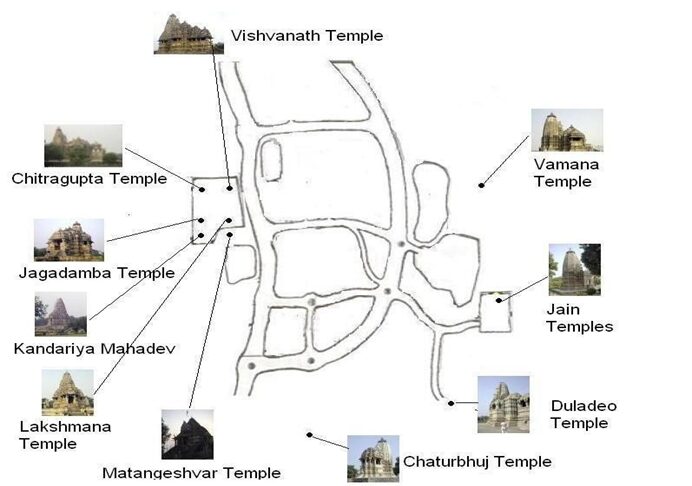

Introduction to Khajuraho temples

The Khajuraho complex is well known for the art and architecture of its temples. The Chandelas rulers, who started building the temples, had the entire area surrounded by a wall. The wall had almost eight gates, most of which were used for entering and exiting. Each gate was said to be encircled on each edge by date palms. The name came from these trees, and the temples have been known as “Khajura-vahika.” ‘Khajura’ indicates ‘Date Palm’ and ‘Vahika’ indicates ‘Bearing’ in Hindi. This region is widespread with Date Palm trees.ii Khajuraho was the cultural capital of the Chandelas. It is believed that there were a total of 85 temples were constructed in the reign of Chandela rulers but out of them, only 24 temples are survived today. Whereas, Lakshman temple is situated in the western group of the Khajuraho complex. With temples and tanks, Khajuraho was largely a site of worship. It was a bustling religious and cultural center oriented to humanitarian acts, where religious scriptures were pronounced, dance and music were played, and people came to find healing. One of the three important temples was the Lakshmana temple.

Interior of the Temple

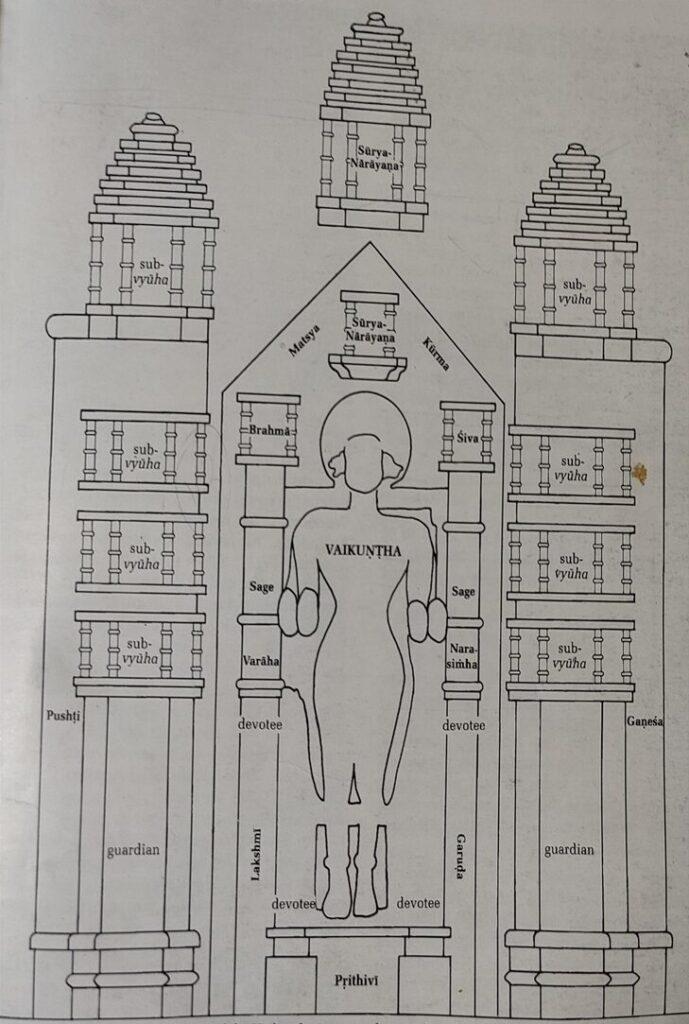

The Khajuraho inscriptions provide valuable information regarding the installation of the Vaikuntha Vishnu image by King Yashovarman. Architecturally, the Lakshman Temple follows the panchayatana plan, consisting of a principal shrine housing the presiding deity and four subsidiary shrines positioned at the four corners of the complex.

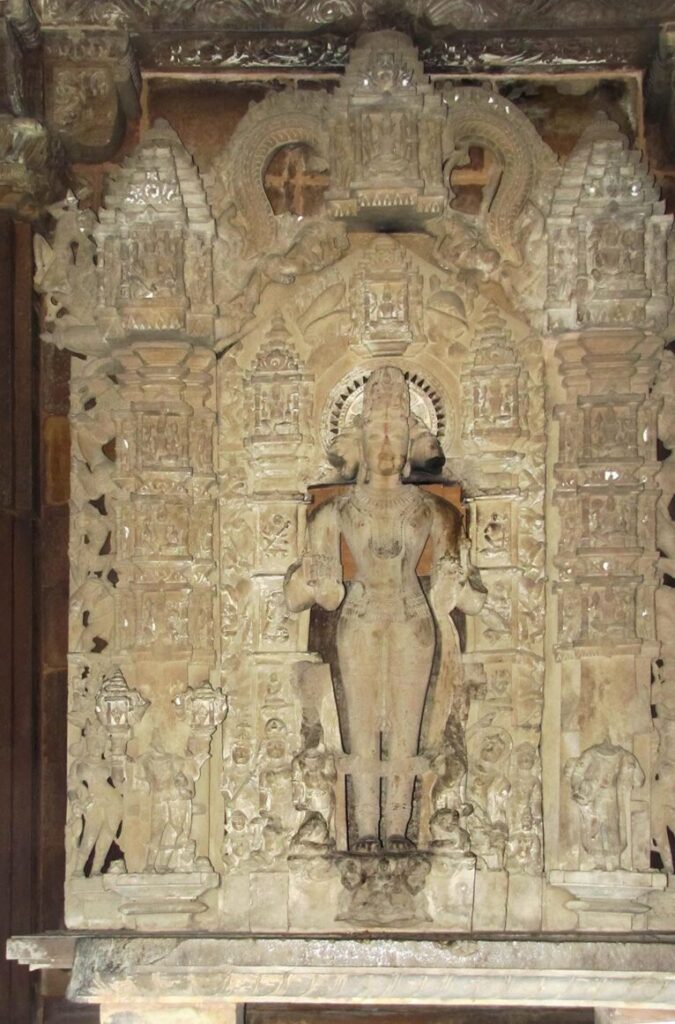

The sanctum (garbhagriha) enshrines a three-faced image of Vaikuntha Vishnu, who is described in the inscriptions as Daityari, the destroyer of demons. The central face represents Vishnu in his placid (saumya) form, while the left face depicts Narasimha (lion) and the right face Varaha (boar), symbolizing Vishnu’s protective and redemptive powers.

Iconography: The image measures approximately 1.21 meters (4 feet) in height and stands upon a sixteen-petalled lotus pedestal. The deity is richly adorned with elaborate ornaments, including padangada leg ornaments, anklets composed of four plates, and a heavy necklace with a double-looped girdle. Arm ornaments (bajubandha) further enhance the sculptural richness. Behind the head appears a halo-like chakra with twenty-five radiating spikes, enclosed within an outer circular frame.

Physiognomy: The central face conveys serenity and benevolence, with large expressive eyes, upward-curving eyebrows, and a composed countenance. Although the nose appears damaged, the overall facial expression remains calm and dignified. The neck displays a double fold, lending a naturalistic quality to the figure. The deity’s broad shoulders, powerful arms, slender waist, and elongated legs emphasize youthful strength and divine vitality, despite minor damage to the arms.

Parikara Frame: Surrounding the main image is an elaborate parikara (iconographic frame), organized into inner and outer zones that articulate Vishnu’s cosmic hierarchy. In the inner frame, Surya-Narayana appears above Vaikuntha in dhyana mudra, flanked by Matsya (fish) and Kurma (tortoise) avatars, symbolizing Vishnu’s supremacy over cosmic evolution. At the level of the head, Brahma is positioned on the viewer’s left and Shiva on the right, representing the triad of cosmic functions—creation, preservation, and destruction. Below them are sages devoted to Vishnu, followed by the Varaha and Narasimha avatars. At the base, devotees are shown at the feet of the deity, expressing submission and reverence. Garuda, Vishnu’s divine vehicle, is depicted near the left leg, smiling in devotion toward his lord.

Pancharatra System: The iconographic arrangement of the sanctum follows the Pancharatra theological system, which is based on the principle of divine emanation. This system presents a hierarchical progression of manifestations, descending from the supreme absolute (Para-Brahman) to the material realm (Prithvi-tattva). Each form emerges from the preceding one, reflecting the cosmic order and explaining the presence of vyuhas and avataras within the temple’s sculptural program.

Coming towards the most imperative point of the inner frame i.e. Earth Goddess; There is a snake hooded goddess who is seated on a tortoise on Vaikuntha’s pedestal. The goddess is identified as a Lakshmi (by R. Awasthi & Krishna deva), represented on the pedestal of all Vishnu images in Khajuraho and central India.

She holds a pot in her left hand, some artisans suggested that she is Prithvi (earth goddess) which is mentioned in the Matsya Purana. Latter Purana states that Vishnu fights with the demons in the form of Varaha. But in Lakshman temple, Vaikuntha is represented as supreme overall, whose four manifestations combine to conquer evils and demons.

Outer frame – In this frame, there is a representation of sub-vyuhas (emanation) in the sanctum. At the topmost you will see the Surya-Narayana of the outer frame, he is seated in Yogasana (with a lot of consent) posture. He is held by Matsya and the Kurma of the inner frame. Total of 8 vyuhas, the eighth one is Chaturvimsati which is the combination of twentyfour images and some of them are Narayana & Kesava, Vasudeva, Vamana, and Aniruddha.

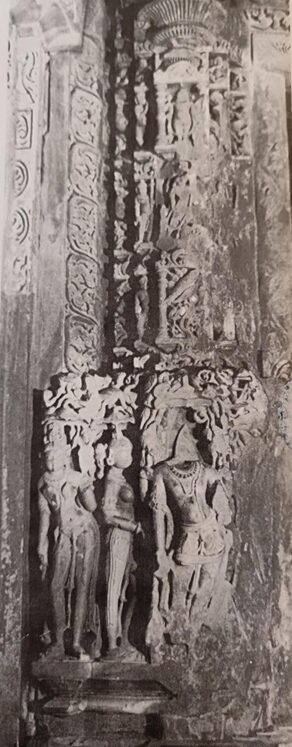

Dvaradevatas – This door located at the entrance of garbhagriha which is depicted deities according to pancharatra system and in simpler form we can say it is door of divinities.

The iconographic program of the sanctum doorway begins at the lintel (lalatabimba). At its center is a representation of Goddess Lakshmi flanked by elephants, symbolizing prosperity and auspiciousness. To the viewer’s left appears Brahma, while Shiva is positioned on the right. Interspersed among these principal deities are finely carved figures of vina players and celestial dancers, enhancing the sacred and celebratory character of the entrance.

Descending from the lintel, the doorway reveals a systematic depiction of Vishnu’s incarnations, arranged symmetrically with three avatars on each side. On the viewer’s left are Vamana (the dwarf Brahmin), Varaha (the boar), and Matsya (the fish), while the right side presents Parashurama (the warrior sage), Narasimha (the man-lion), and Kurma (the tortoise). These incarnations frame the entrance to the sanctum, reinforcing the theological significance of the central deity enshrined within. Below the avatars are the river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna, positioned on either side of the doorway. According to Hindu belief, their presence purifies devotees as they enter the sanctum. Accompanying them are two dvarapalas (door guardians), Dhata and Vidhata, sculpted in high relief and attached to the pilasters, serving as protectors of the sacred space.

A niche beneath the entrance (udumbara)has the figure of a potbellied deity sitting in lalitasan a, carrying a satchel in his right hand and wearing Karanda-Mukta. Despite the fact that the inscription speaks about the devotion to Kshetrapala at this location, appears to be Kubera.

Wall of the Garbhagriha

The sanctum (garbhagriha), with its articulated projections and recesses in plan and their rhythmic continuation in elevation, assumes the appearance of a three-dimensional yantra. The walls are systematically divided into two sculptural registers. At the eight cardinal and intermediate directions, the dikpalas—positional deities such as Indra, Agni, and others—are depicted guarding the sanctum against malevolent forces. These guardian deities are placed on the projections of the lower jangha, while the upper jangha features representations of the eight Vasus, identifiable by their bull-headed forms.

Additional sculptural elements further enrich the wall surface. Vyalas occupy the recesses of the lower jangha, while the upper jangha is animated by twelve narrative panels depicting episodes from the Krishna-lila, integrating mythological storytelling with architectural rhythm.

Cardinal Niches of the Lower Register

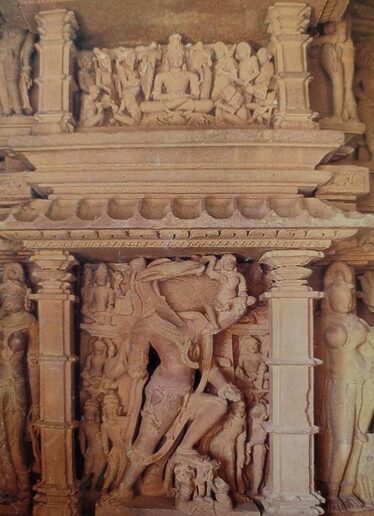

The cardinal niches (ghana-dvaras) of the sanctum are dedicated to major incarnations of Vishnu. In the southern ghana-dvara, Varaha is shown rescuing the Earth Goddess, who rests upon his raised elbow, symbolizing cosmic salvation. The western ghana-dvara depicts a powerful, twelve-armed Narasimha slaying the demon Hiranyakashipu, representing divine justice. In the northern ghana-dvara, the horse-necked incarnation Hayagriva stands in samabhanga. His lower right hand is shown in varada mudra, while the upper right hand holds a mace; the left arms are damaged, indicating later loss or mutilation. While the varaha image is in the southern ghana-dvara, the varaha face of the vaikuntha image is facing north; similarly, the narasimha image is in the western cardinal niche, but the lion face of vaikuntha is facing south. As a result, there appears to be no direct communication between the boar and lion faces of the vaikuntha image in the sanctum and the varaha and narsimha incarnations depicted on the sanctum’s exterior niche.

In the southern jamb, at the doorway of the sanctum, the door guardian Chanda and the river goddess Ganga on the lower section. The three incarnations of the Vishnu; Matsya, Vamana and Varaha paired along the northern doorframe respectively.

Whereas, in the northern jamb of sanctum, in the lower section, the river goddess Yamuna with her tortoise mount and the door guardian. In the central Sakha; in ascending order, the three incarnations; Narasimha, Kurma, and Parasurama (much defaced), are paired respectively with the three manifestations of the southern doorframe.

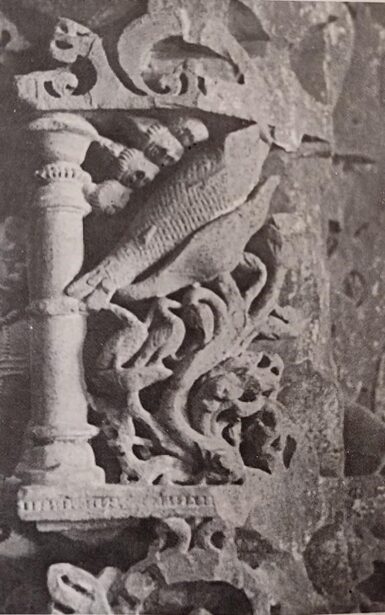

Representation of southern jamb – On the door jamb there is a Matsya incarnation of Vishnu. In mythology, Matsya, like a fish, saves the four Vedas from a demon’s hands. On the back of the fish are the four heads of personified Vedas. The Pancharatra text specifies the location of Vishnu’s incarnations on door jambs.

Vishnu as Varaha rescues the lovely earth goddess from the nether region in the lower niche. She is shown seated on his upper arm’s elbow, her hand gesture praising the lord’s heroic deed. Vishnu-Narayana as kurma is seated in yogasana in the upper niche, surrounded by sage.

Arrangement of images in south elevation of the sanctum– In the upper part of the elevation, the central deity is Vishnu Yogeshvara Kurma and at the viewers’ top-left there is Vasu standing in an S-shaped position. Near this, there are a total of four depictions of Krishna-Lila in the upper part of the elevation and among them, four Surasundaris are enhancing the depiction of Krishna-Lila. Then, there are Vasus and Parvati standing along with the deity in the right. In the lower part of the elevation, the main deity were Varaha in the centre surrounded by Surasundaris and Vyala. On the left side, there is Yama and coming towards the right there are; Agni, Indra and Lakshmi depicted in a sequence.

The sanctum’s northern exterior wall, Hayagriva, the horse-necked incarnation of Vishnu, stands in samabhanga in the lower cardinal niche. Hayagriva is the god of learning who preserved the Vedas in the Panchartra tradition. The upper, partially visible niche depicts Vishnu Yogesvara as Matsya.

Vishnu takes the composite form of Narasimha, a man-lion, who is neither man nor animal, to slaughter the evil king Hiranyakishapu in the twilight when there is neither day nor night. The panel is facing the setting sun. On the top niche, there is a one-of-a-kind depiction of Vishnu yogeshvara being worshipped by Ekantin sages of Sevta Dvipa.

Placement Of Niches In The Garbhagriha

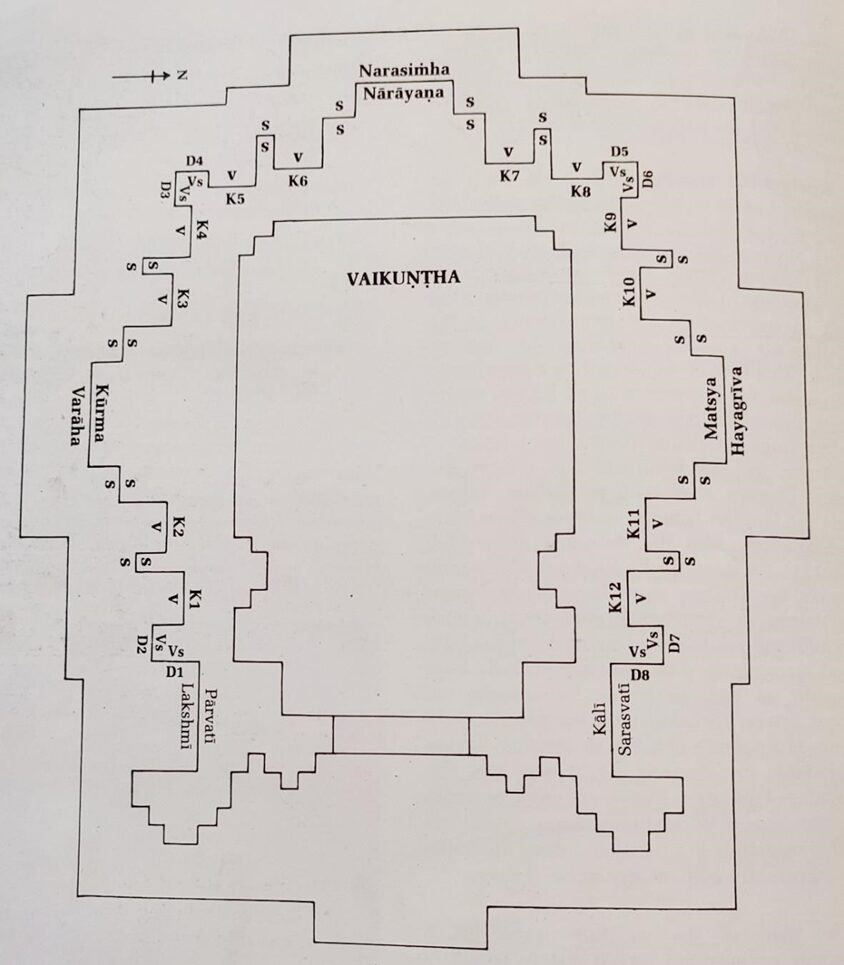

On the three sides of the sanctum, there are 8 vasus, 8 dikpalas, 12 Krishna-Lila scenes, 12 vyalas, 24 sundaris, and Vishnu’s incarnatios. In which in the inner sanctum there is a depiction of 12 krishna lila; in the south wall, 1- 4 krihsna lila scences represented in which trivarta incarnation slaying the storm demon, etc., on the west wall, 5 – 8 depictions from lord krishna’s life, in fifth one, he fought with kaliya at the river Yamuna at Vrindavan. Likewise, the remaining numbers of plays are represented there. Coming on the northern wall, illustrations from 9 – 12, in one of them putana vadh had been represented. In the northwest and southwest corners, there are vasus figures depicted but on the exterior of the sanctum, the images of dikpalas, surasundaris, and vyalas are represented.

[K = Krishna-Lila; K1 = Trivavarta-vadha; K2 = Balarama slays Suta; K3 = Chanura-vadha; K4 = Krishna slays Kuvalayapida; K5 = Kaliyadamana; K6 = Krishna defeats Sala; K7 = grace on Kubja; K8 = Sakatabhanga; K9=Arishtasura-vadha; K10 = Yamalarjuna; K11 = Putana-vadha; K12 = Vatsasura-vadha; D = Dikpala; D1 = Indra; D2 = Agni; D3 = Yama; D4 = Nirriti; D5 = Varuna; D6 = Vayu; D7 = Kubera; D8 = Isana; S = surasundari; V = vyala; Vs = vasu.]

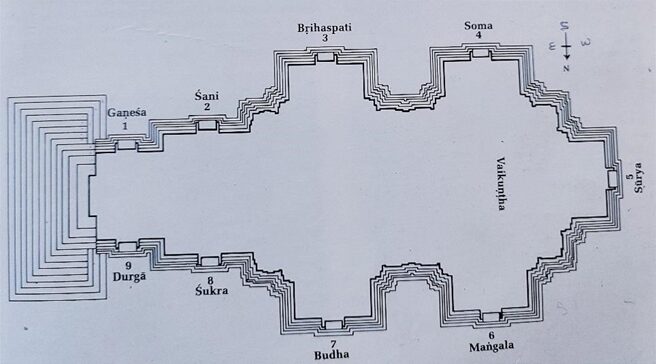

Maha-Mandapa And Pradakshina Path

The maha-mandapa functions as the principal assembly hall in a Hindu temple. In the Lakshman Temple, the architectural components of the maha-mandapa are crowned with pyramid-shaped superstructures. Among these, the tower above the sanctum rises highest, while the porch (ardha-mandapa) is marked by the lowest elevation. Encircling the sanctum is a covered passage that enables ritual circumambulation.

The pradakshina-patha is the circumambulatory passage surrounding the garbhagriha and serves as a sacred route for devotees to ritually engage with the deity. This act of circumambulation facilitates a holistic and symbolic communion between the devotee and the divine.

Within the maha-mandapa and along the pradakshina-patha are placed fourteen surrounding deities (avaranas) associated with Vaikuntha Vishnu, arranged according to theological hierarchy and spatial symbolism.

The Fourteen Avaranas of Vaikuntha

1. Karttikeya – Depicted as an adolescent deity with three heads and four arms, Karttikeya stands in tribhanga. He holds a manuscript in his upper left hand, while the lower left rests on the shoulder of a female figure; his right hands are shown interlocked.

2. Shiva – Positioned adjacent to Karttikeya, Shiva is represented with his vahana Nandi, who appears on the pedestal, emphasizing his role as a principal Shaiva presence within the Vaishnava framework.

3. Chandika – Seated in lalitasana on a lotus pedestal with her lion mount below, Chandika wears her hair in jata. She holds a damaru, trisula, sword, and akshamala in her right hands, and a manuscript, snake, shield, and skull-cup in her left, embodying both protective and destructive aspects.

4. Parvati – Installed in an antarala niche, Parvati stands in samabhanga, holding a lotus and garland. She is accompanied by a seated Ganesa on one side and an attendant holding a bell on the other.

5. Tripura – Represented in an upper niche, this four-armed goddess—identified as a form of Gauri—holds varada, ankusha (goad), pasha (noose), and patra (vessel). She is seated in padmasana upon a lotus pedestal.

6. Amba – Shown as a maternal figure, Amba is seated in lalitasana, gently gazing at the child she holds. She wears a large jata-mukuta and an ornate crown, symbolizing nurturing divinity.

7. Kshemakari – An eight-armed mother goddess associated with health and well-being, Kshemakari holds a sword, trident, conch, goad, spear, and water-pot. She is seated in lalitasana and adorned with a jata-mukuta.

8. Balarama – Standing in the north-western corner of the pradakshina-patha, Balarama is four-armed, holding a cup in one hand and a jar in another. Images of Kubera appear on the serpent hoods above him and on the pedestal.

9. Mahishasuramardini – The ten-armed goddess is depicted slaying the buffalo demon Mahishasura. She stands firmly with one foot upon the demon’s body, wielding weapons that signify the triumph of divine power over chaos.

10–12. Lakshmi, Shiva–Parvati Marriage, and Sarasvati – In the antarala niche, Gaja-Lakshmi and Sarasvati are paired, marking the second such pairing after the sanctum’s kapili. Nearby is a vivid depiction of the marriage of Shiva and Parvati. Lions and Nandi appear on the pedestal, joyfully participating in the ceremony. Significantly, this scene is placed adjacent to the depiction of Parvati’s penance, maintaining symbolic continuity between asceticism and union. The marriage scene, positioned between the sanctum and maha-mandapa, signifies the spiritual union of deity and devotee.

13. Vamana – The dwarf incarnation of Vishnu, described in the temple inscription as the one “who deceives Bali,” is placed near the end of the avarana circuit in the north-eastern corner.

14. Visvarupa – Paired with Vamana, Visvarupa represents Vishnu’s cosmic form. He possesses fifteen heads, including a central human face flanked by lion, boar, fish, and tortoise forms, with nine additional human heads above. Standing in tribhanga and bearing twelve arms, the figure is sculpted in the style of Vaikuntha, expressing the boundless and universal nature of the deity. The juxtaposition of the dwarf Vamana with the cosmic Visvarupa highlights Vishnu’s dual manifestations—humble and infinite.

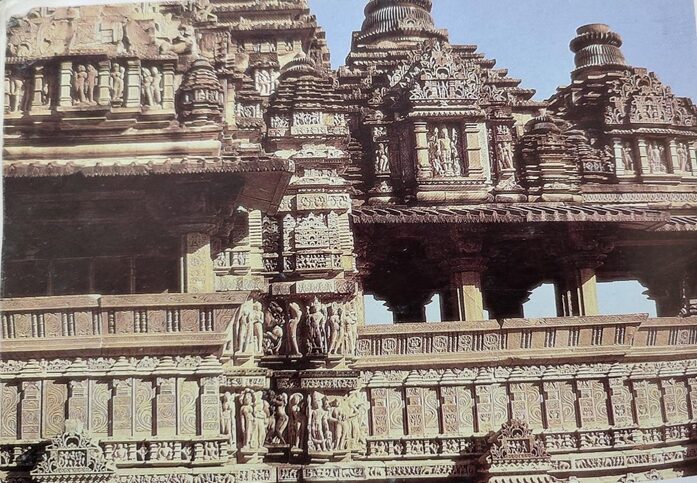

Exterior of the Temple

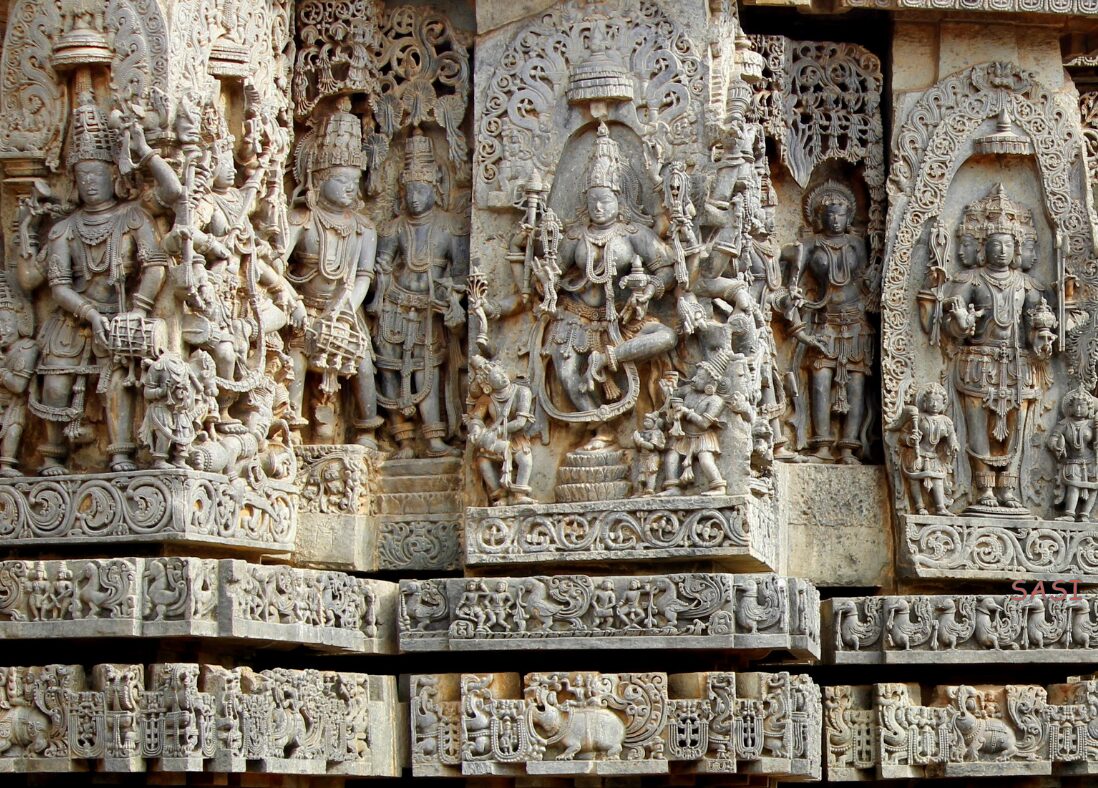

The exterior of temple is filled with sculptural representations. In this picture, we see: that the temple is divided into three sections: the basement moldings with the placement of navgrahas(nine planet) as niches, the jangha(wall) which is divided into two rows of sculpture and last the uppermost part – the superstructure.

1.Mahapita (Basement) – in this, we discuss the placement of nine sculptures depicted as a Navgraha’s deity.

From the southern side, pradakshina wise with an image of dancing Ganesha, to the northern niche representing Durga-Kshemankari with two lions we find seven niches. In this group of seven, central deity is the surya. Six graceful gods with jata are represented by these six niches. They are all four-handed and hold manuscripts in their upper left hand. All six figures have a mutilated lower left hand. Four of the six images show the right hand in varada-cumakshamala (rosary). Two figures on the plan, as illustrated by their hand gestures, conveys knowledge.

The graspattika row of the mahapita has 26 miniature niches. Ganesa is the first image in the series, followed by kubera, Vaishnavi, Parvati, brahmani, Lakshmi, Sarasvati, ardhanarisvara, siva and other divinities.

2. Jangha (exterior wall) – The sculptures on the jangha are organised in two horizontal rows. Vishnu’s Vyuhantara aspects, surasundaris and vyalas are inevitably depicted in the upper row. Standing Vishnu in tribhanga, holds Padma (lotus), Sankha (conch), Gada(mace), and chakra(wheel) and wear kirita-mukuta in various combinations of the Chaturvimsati murtis (24 sculpture) of Vishnu Vyuhantaras. And in the lower row, there are sculptural representations of shiva, surasundaris, naginis and mithunas.

Surasundaris flank Vishnu on the shore, and Vyala is seen in the wall’s corner. The

Vyuhantara or lesser attributes of Vishnu from his 24 emanations, are represented on the Jangha of the temple. They are lower in the framework than the representations in the cardinal niche, which are closer to the central deity, namely Vaikuntha. In this image, we see Vishnu’s Padmanabha form holding her weapon and ornaments.

The above image, Surya maintained control over the front wall, demonstrating the sun’s powerful connection with Vaikuntha. The sun-bird Garuda was originally surrounded by a front hall and faced this temple.

3.Superstructure (Shikhar)– The front wall of the temple is graced with a beautiful image of Surya. He holds two lotus flowers in his hands. The temple’s inscription emphasizes Surya and concludes with the mantra. The Mukhamandapa’s southern niche depicts an image of Hari-Hara, which is linked up to the north and there is another image of Ardhanarisvara. On the south, the roof of Mandapa depicts Agni with his Ram-Bhana, while on the north it represent Vayu. Alternatively, soma with varada, there also a large group of sculpture with manuscript and water-pot.

In the rathikas of sanctum and Mahamandapa, a human couple replaces the divinities. These four pairs could portray Purusha-Parakriti or Manu-Consort, the couples who assisted in the creation of the universe. In Garbhagriha in the northern niche, we see two males, they are either teacher-learner or father-son or maybe some kind of depiction of tale.

In this image, we clearly see the Mukhamandapa, Mahamandapa, and Mandapa along from the south. In-wall sculptures there is a depiction of the deities: Agni and Hari-Hara and some couple. An old man and an adult acknowledge each other in the image and some figures of females and couples are shown.

Sculptural Representation

The architecture of temple has presented total eight categories of sculpture :-

1-Cult icons – it includes the goddesses placed inside the sanctum.

2-Attendant and surrounding divinities – depiction of cardinal niches in lower row of sanctum in round of high reliefs.

3-Demi-gods – symbolization of celestial world representing dwarfs on the top of row and dynamic flying figures.

4-Celestial women or divine sprite – in every depiction of female sculptures, it shows activites of female nature such as removing a thorn from foot, carries a baby and dancing from body posture.

5-Animals – this sculpture includes the Vahanas of deities and some holistic representations like elephants in the basement.

6-Secular scenes – depiction of hunting scenes, armies, educational and trading scenes at the plinth.

7-Geometric and floral desings – these sculptural designs are used in the decoration of temples for example the ceilings of the inner sanctum and pedestal in a floral lotus pattern or in circular. 8-Erotic sculpture – on the main exterior wall of the temple, erotic scenes with incredible and sensitive metaphors are almost a meter high. There are several theories given for what they depicted: desire (Karma), the goal of life to delight the casual observer, or they are intended to test spiritual strength. Tourist guides frequently claim that they represent body posture from the Kamasutra, but this is not the case because they depict activities (such as oral sex) that are condemned in the Kamasutra, and were more possibly constructed to mock the contemptible practices of extreme Trantic cults. They date back to the ancient population and can be found in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain art, where they are frequently representational. It is suggested that they merge the polar opposites of man and woman, breathing and respiration, and their creation was represented through yoga.

In Chandelas’ time, men have several wives, and women were restricted to their one husband and always stayed in their home. It shows that there was the concept of free love didn’t exist. On the juncture wall, you see a male sculpture performing sexual activities with more than a single figure of female and also couple’s figures. This shows that Chandelas were more focused on spreading sex education during their reign.

Religious Background

The ancient Hindu religion is founded on Sanskrit texts, the Vedas (historical records), and the Upanishads, which emphasize abstract notions rather than deities: Brahman (universal spirit or world soul), Atman (one eternal human soul), and Maya (the cosmic flux which animates all things). The goal was to merge the atman with the brahman in order to free the soul from its karma (successive reincarnations of human and animal forms determined by conduct). The caste system arose from the belief in karma. Brahma (founder of the universe), Vishnu (creator and supporter), and Shiva (destroyer) are all equal in reality and play interchangeable roles in the Bhagavad Gita, which dates from 200 BCE. To put it another way, they reflect the male and female as destruction and creation aspects of the almighty Absolute. In other words, Hindus are not primitive since they worship many manifestations rather than many gods. The incarnations of god can have a direct relationship with humans. Hindu temple construction began in the sixth century BCE and reached its pinnacle during the tenth and thirteenth centuries. The earliest god statues occur around this time, and the Manarara Silpasastra codifies their image. These images can be consecrated and imbued with the holy spirit through the ceremony, but they are not subjects of worship in the traditional sense.

Conclusion

Khajuraho group of monuments mainly have Hindu and Jain temples. We appreciate to Chandella period, who add a masterpiece to our cultural heritage and give a new style to Indian temples. The architecture of this temple is very unique and it represents the creator of this universe, Lord Vishnu. Furthermore, the temple depicts collections of deities and incarnations of Vishnu. It has various platforms in which systematic arrangement of deities and human life depictions are seen. It is said that the construction of the temple depends on Hindu mythologies and Sanskrit Vedas and manuscripts. Today, there are numerous devotees if Vishnu who visit the temple daily. To approach the deity, devotees reach the temple, they started from the east and completed the walk around the entire space, this practice is known as circumambulation. They start walking clockwise all along a large plinth of the temple’s inner platform, beginning at the left of the stairs.

Vaishali Shakya is a museum archivist with a deep passion for preserving cultural heritage. Her work focuses on documenting museum collections and safeguarding heritage and material culture. She holds a Master’s degree in Museology from the Indian Institute of Heritage, New Delhi (formerly the National Museum Institute), and a Bachelor’s degree in Ancient Indian History and Archaeology from Vikram University. Through her research and professional practices, she is committed to making India’s rich cultural heritage accessible to wider audiences.