Ranthambore, nestled amidst the rich cultures of Rajasthan, emerges as a stunning haven where the lush emerald forests meet the echoes of ancient fortresses. In this picturesque landscape, majestic tigers roam freely, and the rich wildlife, steeped in history, defines Ranthambore’s natural magnificence.

Ranthambore is one of India’s beating hearts of Rajasthani history and culture, with an astounding legacy worth beyond imagination. Its royal patronage has influenced Ranthambore’s wildlife, conservation, art, architecture and culture for countless centuries. The royalty of Ranthambore has left a legacy that influences modern conservation and wildlife populations.

Ranthambore, formerly Ranastambhapura, has a long history of Maharajas, with stories of bravery, leadership and valour. The enchanting tales of the Maharajas of Ranthambore unfold with mystique and intrigue.

The first Maharaja of Ranthambore, Maharaja Hammir Dev Chauhan, ruled from 1281 to 1301 CE and was the last king of the Chauhan or Chahamana dynasty, which had ruled over Ranastambhapura. He is known to be the most powerful ruler of Ranthambore. His presence is found in vernacular literature across many scriptures. During the formative years of his rule, the Maharaja was responsible for losing many allies due to his uncontrollable habit of raiding his neighbouring kingdoms. In 1299 CE, Ranthambore was invaded by Alauddin Khalji after the Maharaja gave asylum to Mongol rebels from Delhi. Although the Maharaja’s forces had initial successes against Ulugh Khan and Nusrat Khan, Alauddin’s generals, he was eventually defeated and killed in 1301 CE. He fought a total of 17 brave battles, eventually winning 13, displaying his valour and courage.

After the death of Maharaja Hammir, regional ballads and chronicles, such as the Hammir Mahakavya, celebrated his legacy, characterised by courage and strength, with elements of resistance against Alauddin Khalji. The Hammir Mahakavya or Mahākāvya is a Sanskrit epic poem written by Nayachandra Suri, a Jain poet and scholar. The symbolic poem was composed around the 15th century, which glorifies and immortalises the Maharaja’s patriotic life, battles he fought and his martyrdom. Most notably, the Maharaja strengthened the fortifications of the Ranthambore Fort, enhancing its defences and ensuring the kingdom’s security against external threats.

Maharaja Hammir Dev Chauhan set the perfect stage for all future royal generations of Ranthambore, for he encouraged the tribal cultures and literature to shine. He supported poets and scholars, fostering a vibrant cultural environment, and established himself as an enduring figure in the history of Rajasthan.

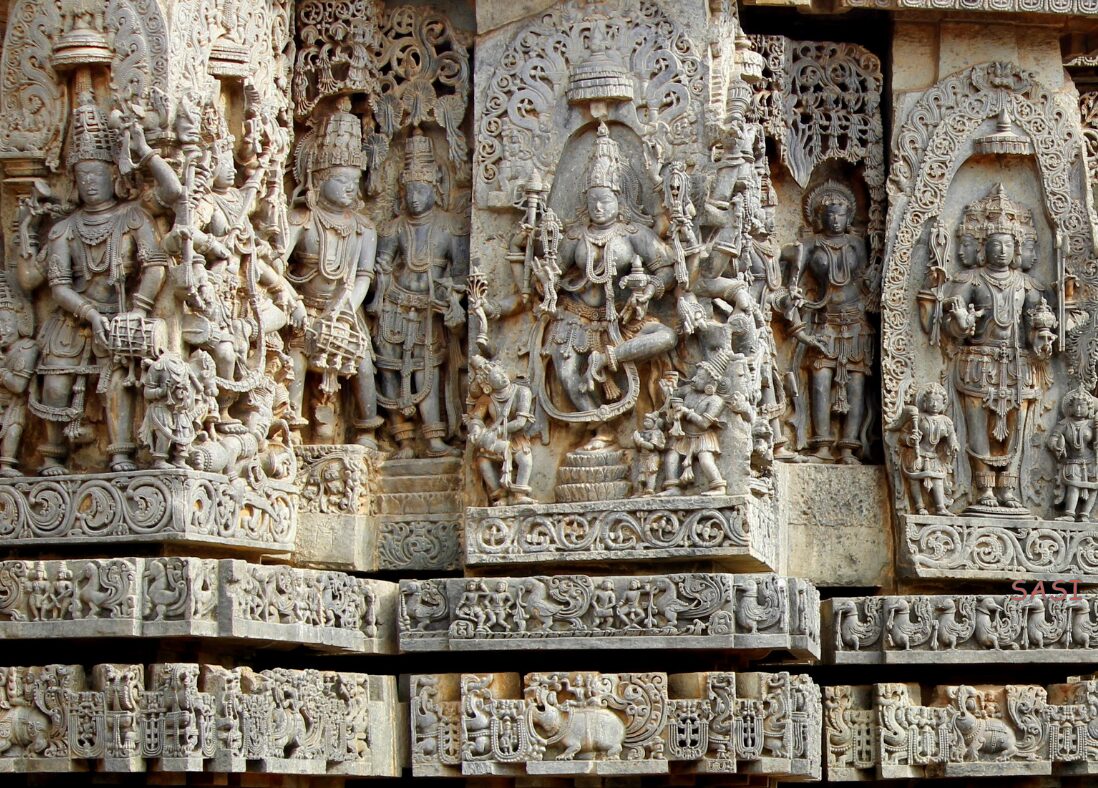

After Maharaja Hammir Dev Chauhan’s reign, many successful and valiant rulers followed, such as Maharaja Rao Raja Karan Singh (1301–1343), Maharaja Rao Raja Ganga Singh (1375 –1425) and Maharaja Rao Raja Bhim Singh (1490 –1530). Amongst these illustrious Maharajas lies one who made his unique mark in history as a loyal general of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, and who served as the governor of Ranthambore under the Mughal rule: Maharaja Man Singh I of Amber. Hailing from the Kaccawaha Rajput subclan of the Suryavanshi Kshatriyas, he belonged to the Dhola line of descent. From 1580 to 1614, he characterised himself as a noble warrior, visionary leader, and wildlife enthusiast, whose regal presence illuminated Ranthambore’s wondrous historical tapestry. He renovated many parts of the fort and converted it into a hunting ground, used to date.

According to historians, it was Maharaja Jayanta who began the construction of the fort during the 5th century. Subsequently, the Rajput King Sapaldaksha of the Chauhan Dynasty continued to fortify the construction of the Fort during the mid-10th century. Today, the magnanimous Ranthambore Fort, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is nestled between two hills, Rann and Thambor. It is predominantly situated on the isolated Thambor hill, around 481 metres above sea level, covering the breathtaking views of the national park. Strategically located, the fort was built for many reasons: to keep enemies at bay, for royal hunting and as a midway stop between large cities in Rajasthan. It is considered one of the strongest forts of India. The fort is nestled within the Ranthambore National Park, near Sawai Madhopur. The grounds of the National Park, as well as the Fort were common hunting locations for the Maharajas of Jaipur until India’s Independence in 1947.

Once the abode of Chauhans, Yadavs, Mughals and Jaipur rulers, the dilapidated structure of Ranthambore Fort displays neglect and disregard. The lack of public awareness, bureaucratic deadlock, and poor heritage preservation have brought this historically significant and architecturally important heritage site to its knees with scant tourist footfall.

Wildlife conservation is well prioritised over heritage preservation. Unlike Ranthambore Fort, Ranthambore National Park, a renowned and well-kept Tiger Reserve in India, is famous for its large Bengal Tiger population. Established in 1955 as a Game Sanctuary, it was once the Maharajas’ hunting ground, but has since evolved into a major wildlife sanctuary and a top destination for nature enthusiasts and photographers. In 1973, the Indian government launched Project Tiger, designating 60 km² of Ranthambore as a tiger sanctuary. The project aimed to eliminate human exploitation and disturbances in the park’s core area, while managing activities in its buffer zones. Ranthambore displays an enchanted and rich tapestry of history, culture and wildlife: a perfect combination on paper. However, while the glorification sounds like music to the ears, Ranthambore’s fort is calling for attention and care. The once-majestic fortification must be preserved to keep as evidence of India’s majestic and royal history, for the generations to come and appreciate.

Tisha Tiwari is a Grade-12 student at The British School, New Delhi, passionate about the study of Modern Indian History and its relevance today. My areas of research include the Saffronisation of Indian Education, the Indian Independence struggle, women in Indian history and the conservation of Indian heritage sites.

Excellent Description

Indeed. Excellent write up by Tisha.